Category Archives: USA

New Year’s Eve World War II

Despite the war raging throughout the world—there were still some times to celebrate some events. The celebrations in this post are impressions of New Year’s Eve in New York in 1941 and San Francisco in 1943.

Sources

https://www.opensfhistory.org/osfhcrucible/2018/12/30/new-years-eve-1943-a-closer-look/

The other side of Abraham Lincoln- A forgotten history

Very few people will dispute that Abraham Lincoln was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, US President. However, his moral values weren’t as pure as many people think they were.

Thirty-eight Native Americans were hanged on Dec. 26, 1862, as ordered by f President Abraham Lincoln, on December 6, 1862 after the 1862 Dakota War, which was also known as the Sioux Uprising of 1862. The sentences of 265 others were commuted.

The Santee Sioux were found guilty of joining in the so-called “Minnesota Uprising,” which was actually part of the wider Indian wars that occurred throughout the West during the second half of the nineteenth century. For nearly half a century, Anglo settlers invaded the Santee Sioux territory in the Minnesota Valley, and government pressure gradually forced the Native peoples to relocate to smaller reservations along the Minnesota River.

At the reservations, the Santee were badly mistreated by corrupt federal Indian agents and contractors; during July 1862, the agents pushed the Native Americans to the brink of starvation by refusing to distribute stores of food because they had not yet received their customary kickback payment.

On September 28, 1862, two days after the surrender at Camp Release, a commission of military officers established by Henry Sibley began trying Dakota men accused of participating in the war. Several weeks later the trials were moved to the Lower Agency, where they were held in one of the only buildings left standing, trader François LaBathe’s summer kitchen.

As weeks passed, cases were handled with increasing speed. On November 5, the commission completed its work. 392 prisoners were tried, 303 were sentenced to death, and 16 were given prison terms.

President Lincoln and government lawyers then reviewed the trial transcripts of all 303 men. As Lincoln would later explain to the U.S. Senate:

“Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.”

When only two men were found guilty of rape, Lincoln expanded the criteria to include those who had participated in “massacres” of civilians rather than just “battles.” He then made his final decision, and forwarded a list of 39 names to Sibley.

At 10:00 am on December 26, 38 Dakota prisoners were led to a scaffold specially constructed for their execution. One had been given a reprieve at the last minute. An estimated 4,000 spectators crammed the streets of Mankato and surrounding land. Col. Stephen Miller, charged with keeping the peace in the days leading up to the hangings, had declared martial law and had banned the sale and consumption of alcohol within a ten-mile radius of the town.

As the men took their assigned places on the scaffold, they sang a Dakota song as white muslin coverings were pulled over their faces.

Drumbeats signalled the start of the execution. The men grasped each others’ hands. With a single blow from an ax, the rope that held the platform was cut. Capt. William Duley, who had lost several members of his family in the attack on the Lake Shetek settlement, cut the rope.

After dangling from the scaffold for a half hour, the men’s bodies were cut down and hauled to a shallow mass grave on a sandbar between Mankato’s main street and the Minnesota River. Before morning, most of the bodies had been dug up and taken by physicians for use as medical cadavers.

After the execution, it was discovered that two men had been mistakenly hanged. The Minnesota Historical Society reports that “Wicaƞḣpi Wastedaƞpi (We-chank-wash-ta-don-pee), who went by the common name of Caske (meaning first-born son), reportedly stepped forward when the name ‘Caske’ was called, and was then separated for execution from the other prisoners. The other, Wasicuƞ, was a young white man who had been adopted by the Dakota at an early age. Wasicuƞ had been acquitted.

Although Abraham Lincoln oppose slavery, his in laws were slave owners albeit reluctant.

Lincoln the politician did not recognize blacks as his social or political equals and, during his years as a lawyer and office seeker living in Illinois, his opinion on this did not change. Lincoln was opposed to the institution of slavery during his entire lifetime but, like most white Americans, he was not an abolitionist. In ante-bellum America, abolitionists were a marginal, radical group, and most white Americans did not participate in or endorse abolitionist activities.

He was a man of contradictions, but this probably is what made him the great leader he became.

sources

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2206706

https://apnews.com/article/archive-fact-checking-2786870059

https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/abraham-lincoln/

https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/aftermath/trials-hanging

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

Americans and the Holocaust

Americans and the Holocaust is an exhibition at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, which opened on 23 April 2018. Before I go into the details of this exhibition, I want to mention one of the few Americans, Eddy Hamel, who was murdered during the Holocaust.

Eddy Hamel was the first Jewish player, and also the first American, to play for Ajax in Amsterdam. Born in New York City in 1902, he had moved to the Netherlands as a baby with his Dutch-born parents and considered himself more Dutchman than American.

Hamel became a first-team regular for Ajax, to date, only four other Jewish soccer players have followed in his footsteps—Johnny Roeg, Bennie Muller, Sjaak Swart, and Daniël de Ridder. Hamel was a fan favourite and was cited by pre-World War II club legend Wim Anderiesen as part of the strongest line-up he ever played with. He had his fan club in the 1920s, which would line up on his side of the field at the beginning of every game and then switch sides—to be on the side of the field he was on during the second half. After his retirement as a player, Hamel managed Alcmaria Victrix for three years and continued to play in an Ajax veteran squad.

Hamel became a first-team regular for Ajax, to date, only four other Jewish soccer players have followed in his footsteps—Johnny Roeg, Bennie Muller, Sjaak Swart, and Daniël de Ridder. Hamel was a fan favourite and was cited by pre-World War II club legend Wim Anderiesen as part of the strongest line-up he ever played with. He had his fan club in the 1920s, which would line up on his side of the field at the beginning of every game and then switch sides—to be on the side of the field he was on during the second half. After his retirement as a player, Hamel managed Alcmaria Victrix for three years and continued to play in an Ajax veteran squad.

Hamel, his wife and their sons lived across town at the time, not far from where 13-year-old Anne Frank and her family lived. In apparent defiance of the rules of the Nazi regime, Hamel continued to play for his old team. Lucky Ajax, during the German occupation.

On 27 October 1942, Hamel was stopped by two officers from the Jewish Affairs division of the Amsterdam Police Department, which collaborated with the Nazis. The arrest report, written in German, states that Hamel told his captors he was born in New York. He gave coaching as his profession. The reason for the arrest: He was caught in public ohne judenstern—without his Jewish star. Despite his American citizenship, Hamel was detained by the Nazis because he was a Jew.

Eddy and his family had to report to Westerbork. They ended up in the so-called English Barrack. There were British and American citizens who were eligible for exchange. But that status turned out to offer no protection either. Leon Greenman, who was in the same barracks, spent the last few months with Eddy. Both their families were deported to Auschwitz in January 1943, where the women and children were immediately murdered. Both men were to work.

Eddy spent four months doing hard labour at Birkenau. After he was found to have a swollen mouth abscess during a Nazi inspection, the Nazis sent him to the gas chambers in Auschwitz concentration camp on April 30, 1943, where they murdered him.

AMERICANS AND THE HOLOCAUST

By the time Nazi Germany forced the world into war, democratic civilization was at stake. The US military fought for almost four years to defend democracy, and 400,000+ Americans died. The United States alone could not have prevented the Holocaust, but more could have been done to save some of the lives of the six million Jews killed.

It was already known in 1933 what was happening in Germany. The photograph at the top of this post is from a resolution sent on 27 March 1933 by the United Churches of Lackawanna County in Scranton, Pennsylvania, to US Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

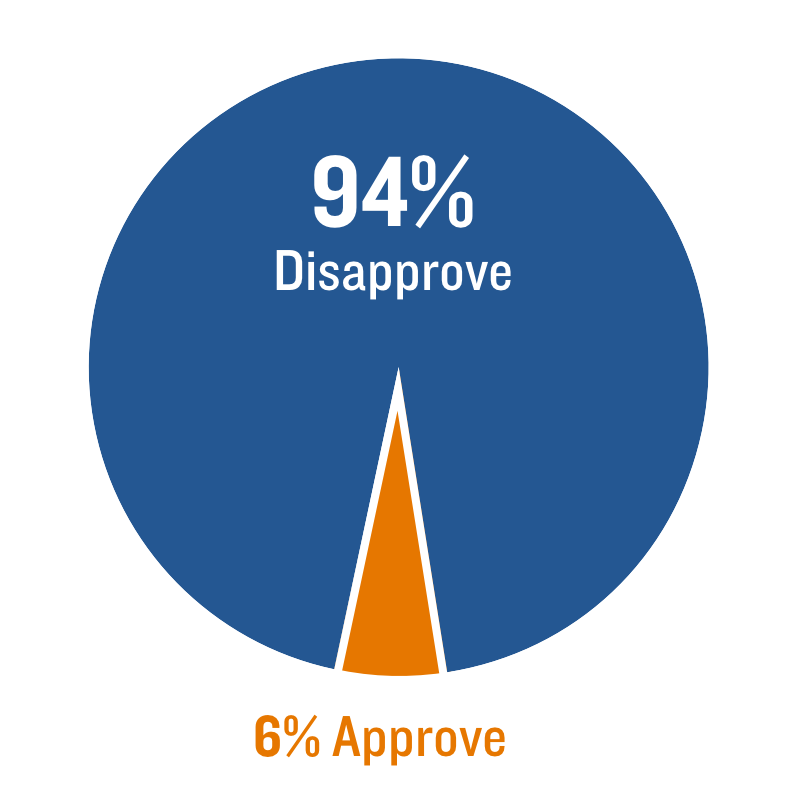

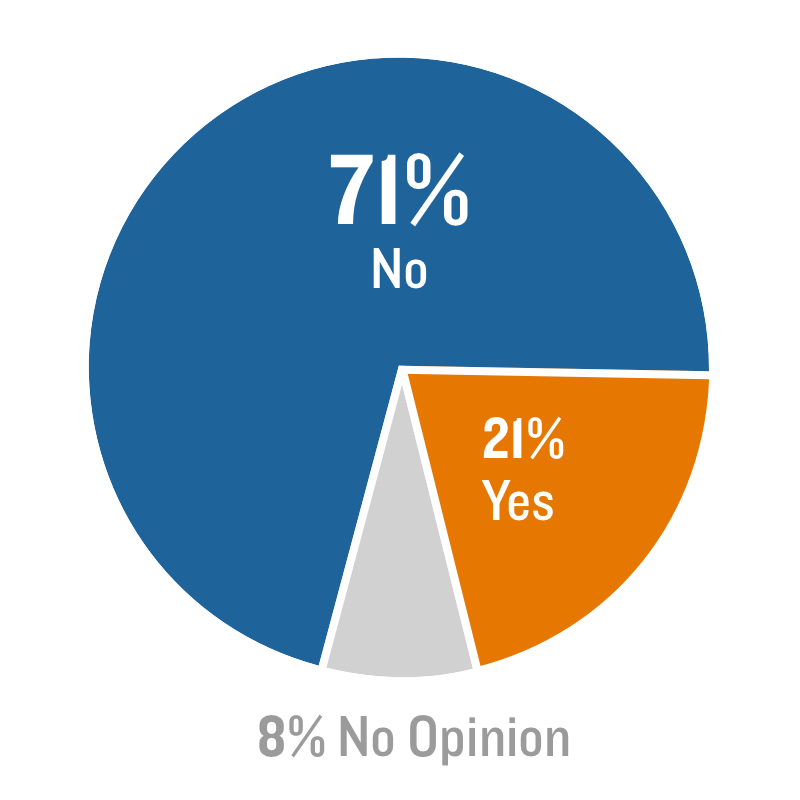

After Kristallnacht, Gallup asked Americans: Do you approve or disapprove of the Nazi treatment of Jews in Germany? Of the vast majority who responded, 94% indicated disapproval. Yet, although nearly all Americans condemned the Nazi regime’s terror against Jews in November 1938, that very same week, 72% of Americans said, No when Gallup asked: Should we allow Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live?—only 21% answered Yes.

Prejudice against Jews in the U.S. was evident in several ways in the 1930s. According to historian Leonard Dinnerstein, more than 100 new anti-Semitic organizations were founded in the U.S. between 1933 and 1941. One of the most influential, Father Charles Coughlin’s National Union for Social Justice, spread Nazi propaganda and accused all Jews of being communists. Coughlin broadcast anti-Jewish ideas to millions of radio listeners, asking them to pledge to restore America to the Americans.

On 20 November 1938, two weeks after Kristallnacht, Coughlin, referring to the millions of Christians killed by the Communists in Russia, said, “Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted.”

Further to the fringes, William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Legion of America (“Silver Shirts”) fashioned themselves after Nazi Stormtroopers (“brownshirts”). The German American Bund celebrated Nazism openly, established Hitler Youth-style summer camps in communities across the United States and hoped to see the dawn of fascism in America.

Even if the Silver Shirts and the Bund did not represent the mainstream, Gallup polls showed that many Americans held seemingly prejudicial ideas about Jews. A remarkable survey conducted in April 1938 found that more than half of Americans blamed Europe’s Jews for their own treatment at the hands of the Nazis. This poll showed that 54% of Americans agreed that “the persecution of Jews in Europe has been partly their own fault,” with 11% believing it was “entirely” their own fault. Hostility to refugees was so ingrained that just two months after Kristallnacht, 67% of Americans opposed a bill in the U.S. Congress intended to admit child refugees from Germany. The bill never made it to the floor of Congress for a vote.

Fritz Kuhn, a German veteran of World War I, was the leader (or Bundesfuher) of the German-American Bund. After World War I, Kuhn immigrated first to Mexico and then to the United States, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1934. At its height—the Bund had organized 20 youth training camps and were promoted as family-friendly summer camps—Camp Siegfried in Long Island, Camp Hindenberg in Wisconsin, and Deutschhorst Country Club in Pennsylvania. They were devoted to projecting favourable views of Nazi Germany and spreading Nazi ideology in the United States. The camps’ popularity increased rapidly. The New Jersey division of the Bund opened its 100-acre Camp Norland at Sussex Hills in 1937, and the annual German Day festivities at Camp Siegfried in Long Island attracted 40,000 people in 1938.

Even during World War II, the American public realized that the rumours of mass murder in death camps were true—struggling to grasp the vast scale and scope of the crime. In November 1944, well over 5 million Jews had been murdered by the Nazi regime and its collaborators. Yet just under one-quarter of Americans who answered the poll could believe that more than 1 million people had been murdered by Germans in concentration camps; 36% believed that 100,000 or fewer had been killed.

Below is an interview with Dr. Daniel Greene, the guest exhibition curator at the museum, where he talks about further polls in the exhibition Americans and the Holocaust.

Finishing up with the story of another Jewish American. He did not die in any of the concentration camps, but he died on the battlefield.

Leo Lichten was born on 31 May 1925, in Manhattan, the son of Max and Mollie Lichten. He grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and his best buddy, Paul, described him as “a very noble, intelligent and courageous person.” He even saved Paul from drowning once when they were kids.

Pfc Leo Lichten entered the service in New York, New York on 11 August 1943. Leo’s company, Company A, was ordered on 20 November 1944, to attack pillboxes (small bunkers) just outside Prummern to eliminate the enemy resistance in the small German town.

The weather was cold and rainy, the ground was muddy, and it made the battle even more difficult than it might otherwise have been. Leo stormed one of the pillboxes and was killed by machine gun fire early on in the battle.

He was laid to rest in the Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial in Margraten, along with 8,300 fellow US soldiers and the names of 1,700 others who went missing in action.

I know there was a lot to read and listen to in this post, but it is important that these stories are remembered and retold.

Sources

https://www.si.com/soccer/2019/02/12/eddy-hamel-ajax-american-holocaust-victim-auschwitz

https://en.margratenmemorial.nl/dossier/leo-lichten/overview.html

https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust/main

https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/232949/american-public-opinion-holocaust.aspx

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

US Public Opinion During and Before World War II

To gauge the feeling of the population on a particular subject, conducting an opinion poll is a powerful tool.

Below are some polls taken in the United States just before and during World War II.

Gallup poll conducted September 1-6, 1939.

How far should we go in helping England, France and Poland …

| Yes | No | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Should we sell them food supplies? | 74 | 27 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Should we sell airplanes and other war materials to England and France? | 58 | 42 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Should we send our Army and Navy abroad to fight against Germany? | 16 | 84 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GALLUP, SEPT. 1-6, 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Polls conducted several weeks after the Kristallnacht attacks found that Americans overwhelmingly disapproved of the Nazi treatment of Jews, but most did not want more Jewish refugees to immigrate to the United States.

Do you approve or disapprove of the Nazi treatment of Jews in Germany?

Should we allow a larger number of Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live?

In September 1939, about two weeks after the start of World War II, Americans expressed considerable scepticism about news reports coming in from Europe. Two-thirds said they had no confidence in the news from Germany, and 30% said they had no confidence in the news from England and France. Fake news and misinformation were an issue then too.

Americans’ Confidence in News From Europe During World War II

Do you have confidence in the news from [England and France/Germany] at the present time?

| Complete confidence | Some confidence | No confidence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| News from England and France | 8 | 62 | 30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| News from Germany | 1 | 33 | 66 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GALLUP, SEPT. 13-18, 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In a Gallup poll conducted days after Japan’s infamous attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, 97% of Americans said they approved of Congress formally declaring war on Japan. Just 2% disapproved.

Do you approve, or disapprove of Congress declaring war against Japan?

| Dec. 12-17, 1941 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Approve | 97 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disapprove | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No opinion | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GALLUP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

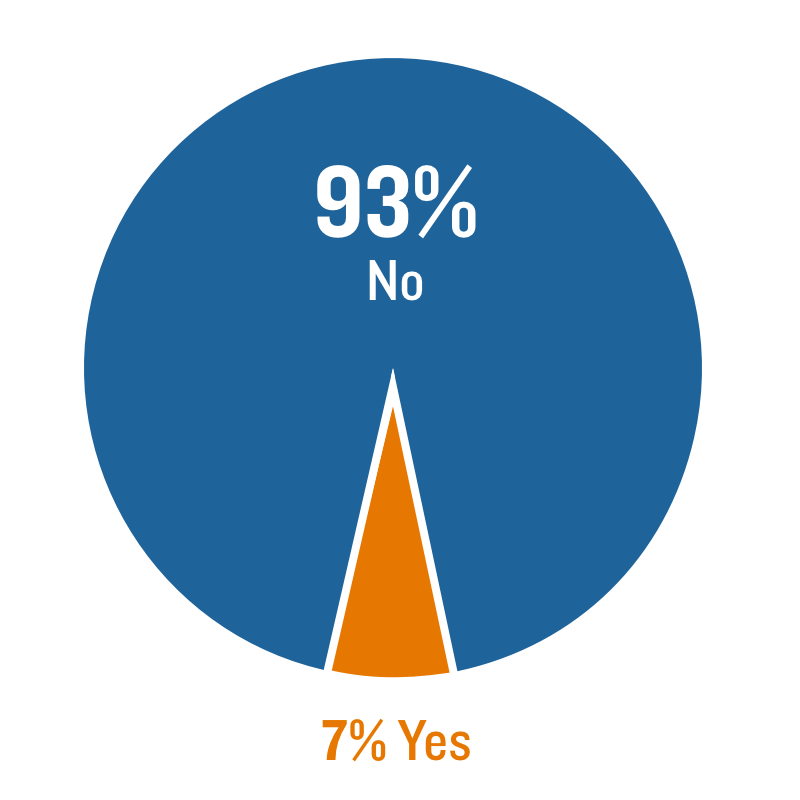

A poll conducted one week after Nazi Germany invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and France showed that Americans overwhelmingly opposed entering World War II.

Do you think the United States should declare war on Germany and send our army and navy abroad to fight?

In December 1942, a year after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and several months after Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast were subsequently “relocated” inland to U.S. detention camps, 48% of Americans believed the detainees should not be allowed to return to the Pacific coast after the war. Just 35% of Americans said they should be allowed to go back.

Do you think the Japanese who were moved inland from the Pacific coast should be allowed to return to the Pacific coast when the war is over?

| Yes | No | No opinion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| December 1942 | 35 | 48 | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GALLUP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In August 1945, just weeks after the U.S. dropped nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, 69% of Americans felt positive about the development of the atomic bomb, saying it “was a good thing.” Just 17% called it a “bad thing.” More recently, attitudes were nearly reversed, with 61% of U.S. adults in 1998 calling the bomb’s development a bad thing and 36% a good thing.

Do you think it was a good thing or a bad thing that the atomic bomb was developed?

| Aug 24-29, 1945 | Jun 5-7, 1998 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Good thing | 69 | 36 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bad thing | 17 | 61 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No opinion | 14 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Based on U.S. adults | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GALLUP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In a Gallup poll conducted shortly before 6 June 6, 1944, the Allied landing in Normandy (now known as D-Day) found that many Americans were unclear about why the U.S. was fighting the war. In the March 1944 poll, 59% of respondents said they had a “clear idea” of what the U.S. was fighting for, while 41% did not.

How much longer do you think the war with Germany will last?

| January 1944 | March 1944 | July 1944 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Will end in 1944 | 58 | 33 | 59 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Will end in 1945 | 31 | 46 | 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Will end in 1946 | 5 | 12 | 6* | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Will end in 1947 or later | 1 | 2 | – | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No opinion | 5 | 7 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources

Martin Haas—The Story of a Survivor

Martin Haas was born Martijn Haas, at the end of 1936 in Breda, a small city in the south of the Netherlands. Just before the war started, about two hundred Jews lived in Breda. Martin survived because his parents kept him safe in hiding. His parents and 2 of his siblings did not survive. His sister Elizabeth and his brother Izaak, together with their mother Margaretha were murdered in Sobibor on 23 April 1943. His father, Jacob Richel was murdered on 28 February 1943 at Auschwitz.

Martijn Haas cries as quietly as he can at night in the dark attic of his hiding place. It is 1942 and World War II is in full swing. Martijn is five years old and he is alone. He does not know where his family is. Martijn nowadays goes through life as Martin, 83+ years old and the only one of his family still alive. Researchers found his family name in a research expropriated homes of Jews. They discovered nine properties belonging to Martin’s family in Breda were all taken away by the Nazis.

Most people in Breda know the Haas family. Jacob, Martijn’s father, has a large network of Jewish, but also non-Jewish friends and acquaintances. This is partly due to the family business Haas Manufacturen, where he sold textiles and delivered them to farmer families in the Breda area by car. A gap in the market, because many people do not yet have a car.

The business is going so well that Jacob invests in real estate with his two sisters Adele and Céline and rents them out. All family possessions are taken away during the occupation years. More houses were taken from other Jewish families in Breda. We discover this in the Verkaufsbücher, the administration of expropriations of Jewish property, which is managed by the National Archives in The Hague. Through post-war documents about the Jewish community of Breda, we know how to trace Martijn in the US. He now lives in San Diego and works as a professor at the University of California, where he has been addressed as ‘Martin’ for years.

Martijn does not find out exactly what happened to his family until the nineties. He tells us why and how he lives until then with all his questions. They pile up from October 1942, when he goes into hiding as a five-year-old.

“Just before my sister Rosa and I are taken to a hiding place, my mother puts me on the dining table. It’s a dark and rainy night. She expressly tells me to shut up. I must never reveal that I am a Jewish boy. Although I am, I have to forget about that for a while. And I do, more or less.”

Martijn says goodbye to his mother in the house of his grandfather’s brother at 42 Speelhuislaan, where they temporarily live. The bomb that the Germans dropped on Terheijdenstraat on Sunday 12 May 1940 destroyed their house. The actual target is the station around the corner, an important strategic point, but the bombers miss their target. Everything is gone, and no one is hurt. Breda was evacuated at that time because the mayor fears a fight between French and German soldiers in his city. However, the Germans advance so quickly that Breda is taken without too much resistance.

Because of that bomb, Martijn’s family lost all their belongings at the start of the war. Martin is then three years old. He is the youngest child of his father and mother, Jacob and Greet. He has two sisters, Elisabeth and Rosa, and a brother, Izaak. His grandmother Elisabeth is also part of the family.

“We move in with my grandfather’s brother right behind the station. On the wide sidewalk opposite the house, I learned to cycle with the boys from the street. And I remember one Friday night, the beginning of Shabbat. My two unmarried aunts Adele and Céline are visiting, as they often do. After dinner, we all sit together at the table and they talk about the situation. It is now war and it is very bad for us Jews. I don’t understand what they say. But after that, I don’t dare go into the hallway to go to the toilet. It’s dark, I think it’s too scary.”

“While we live there, my father has a new house built on the Mauritssingel. Another semi-detached house is in the centre. Our family is in one house number, where my father will also run his business, and my aunts in the other number, where they will start a boarding house. How my father did this in the middle of the war is not entirely clear. Because those ‘dirty dirty rotten Jews’ were not allowed to have a bank account. He must have had gold or a lot of cash. Anyway, the house came off. Once we went there with the whole family. And I remember well that there was a spiral staircase behind the house. This allowed you to go to the kitchen from the outside. Without having to enter the house. For the grocer, or anyone. I loved that so much. And that staircase, it is still there.”

The Haas family never lived in that house. During his search for what happened to his family, Martijn finds a handwritten letter dated 13 July 1942, from his father. In it, he writes to the municipality of Breda that he cannot declare the house completed because it is forbidden for him as a Jewish man to come there. It is an attempt to keep the house out of the hands of the occupier.

At that time, Jews had been banned from owning land and real estate for almost a year. The Dutch Property Administration registers Jewish property and outsources the expropriation and sale of Jewish properties to private individuals. In Breda, the ANBO does that, the abbreviation for General Dutch Property Management. NSB members lead this organization. In the Verkaufsbücher we see that nine properties of the Haas family have been expropriated, five of which are in the name of Martijn’s father and his two aunts Adele and Céline.

The homes at Bavelschelaan 112 and Rozenlaan 48 are the first to be listed as ‘provisionally sold’. That is in the summer of 1942. For 6,708.20 guilders C.v. Meant to buy both properties. This practically turns out to be a neighbour of the family. We see that this person is currently registered at the address Pastoor Pottersplein 39, two streets next to the Speelhuislaan where Martijn and his family live at that time.

It is also diagonally opposite another building of Martijn’s father: Pastoor Pottersplein 31. That house is also sold by the NSB members a few months later. Exactly the same is happening with the buildings at Prins Hendrikstraat 73 and Rozenlaan 40-42. The new owners pay no more than a few thousand guilders, a bargain

Around the same time as the expropriation of the houses, Martijn’s father is arrested. As a member of the Jewish Council of Breda, he managed to get a postponement a few times, but on September 29, 1942, that was no longer possible. He is forcibly taken to a Dutch labour camp in Doetinchem. Three days later, all men from the Dutch labour camps are transported to Westerbork. Martin’s father is there.

Martijn, his mother Greet Vleeschouwer-Haas, and his brother and sisters are also called up a few days later. They have to board the train to Westerbork on October 6 and will be reunited with their father there. However, his mother acts differently and thus changes the fate of Martijn and his sister Rosa.

“The evening before we were to be transported to Westerbork, Mrs Hees comes to our house. It is early evening, six o’clock, half past six. It’s raining and it’s dark. Mrs Hees wears a large black cape when she enters. My mother tells me that the two smallest children go with this lady. That’s me and my sister Rosa, whom I call Roosje. Two children could come along and the mother thought, ‘the smaller they are, the greater the chance that the surroundings of the hiding place will not get suspicious.’ And she was right about that.”

“We hide under Mrs Hees’s black cape and walk to the station together. There we take the train to Bergen op Zoom, about 40 kilometres from Breda. There is a lady waiting for my sister. Roosje goes with her to the Baars family, where she was supposed to stay. I continue with Mrs Hees to her house. It was then thought that we would only stay for a few months.”

“The first thing that needs to be done with the Hees family is choosing a name. I will be the seventh child in the family and will have a few options. I choose ‘Brother’, then a very common name. Because I’m blonde, I could easily pass for one of the Hees’ kids, but I don’t go to the same Catholic primary school. No matter how risky it is, Mrs Hees arranges a place for me at the public school in our street, the Coehoornstraat.”

“A heroic act, I later learned. Because I had no papers, my teacher had to be involved in the plot. And especially because Mrs Hees prevents Roosje and me from accidentally betraying ourselves when we meet in the schoolyard. She goes to a Catholic primary school.

Martijn leads a fairly normal life during the war. He learns to read, write and count, likes his teacher, and plays in front of the house of the Hees family with his friends. No one knows that he is a Jewish boy. He acts just like the rest. But at night it is different. Then Martijn can’t distract himself with schoolwork or focus on being a good boy. And he is overcome by loneliness, fear and uncertainty.

“I was still young, but to a certain extent, I knew what was going on. At night, in the dark attic where I sleep, I wonder how my family is doing. I’m very concerned. Where are they, what would happen to them? I cry as quietly as I can. I still carry that feeling with me. That is not going away.”

It will be years before Martijn gets answers to his questions. On the night he flees, his mother goes into hiding with Martijn’s sister Elisabeth and brother Izaak at a bakery in Princenhage, another part of Breda. His aunt, Rosa Vleeschouwer, goes with them. They are good there until the wave of betrayal in February and March 1943. The Sicherheitspolizei (SD) raids the bakery on 11 March 1943, at 11 a.m. His mother and his aunt just manage to get away with the children through the back door, but just before they reach the Bredase forest, the SD agents catch up with them.

The agents pick them up, interrogate them and take them to the detention house. They are then deported via Vught to Sobibor. Aunt Rosa is murdered there less than a month later. The same thing happened to Martijn’s mother, sister and brother a few weeks later. Elisabeth and Izaak are then 10 and 9 years old, Greet is 36. Martijn’s father has been deceased for two months. After Westerbork, he was transported to the labour camp in Auschwitz. He is 42 when he dies.

Before the end of 1943, Martijn has lost almost all of his relatives. Aunt Céline dies in the summer due to illness at her hiding place in Breda. And his aunt Adele dies a month and a half later in Auschwitz. His nephews, nieces and their families do not survive the war either. Martijn’s grandmother did not have to experience the worst part of the war, she died in the summer of 1940. She was already gone when the war really started. Martijn will only find out about all this much later.

Despite the fact that they are both in hiding in Bergen op Zoom, Martijn and Roosje do not see each other during the war. They do send each other letters, which the underground brings back and forth. “I also occasionally receive a letter from the underground itself. From a lady who made contact for my hiding place. She helped both my mother and Mrs Hees during and after the pregnancy and uses her network to help Jewish children. I always cry when I read her letter. And it doesn’t even say anything important, not even her real name.”

Bergen op Zoom is liberated on October 27, 1944.

The north of the country has to wait until after the hungry winter. On 5 May 1945, the whole country is free. Martijn then went into hiding with the Hees family for almost three years. It is waiting for a family member to pick him up.

“I dreamed, hallucinated, that my parents came to get me. Even when none of my family returned, it remained that way. Because no one told me what really happened to my family. That I and Roosje were entitled to the property that had been taken from us, all the homes that had been expropriated, was not my concern. I was too young and focused on catching up on my schoolwork. Meanwhile, I kept hoping that a mistake had been made. That one day my family suddenly walked into the street. That it was all a big misunderstanding.”

There appears to be an uncle on his mother’s side who also survived the war with his wife and two sons. His name is Dick Vleeschhouwer. Martijn goes to Amsterdam to become the third child in the family.

“They had also been in hiding, but the war was so terrible for them that they decided not to be Jews anymore. When I came to them, they were already Christian. They sent me to a strict Christian private school because they thought it was best. But for me, that was a very bad year. It did not work. They couldn’t handle having me, a deeply traumatized child, there.”

“I returned to the Hees family, but staying with them was not an option either. Mrs Hees wanted me to grow up as a Jewish boy, with my ‘own people’. I had to get a good education, also in my own religion. I shook that off then, remembering what my mother had impressed upon me just before I left. But Mrs Hees turned out to be the smartest of the two of us.”

A grandniece of his mother, Beppie Kogel, eventually finds Martijn. She and her husband Ben Oudkerk decide to adopt him. They do not have children of their own yet and would also like to take care of Roosje so that the brother and sister can grow up together. The hiding family Baars would like Roosje to stay with them. They already had her baptized during the war and she follows Catholic education just like their children. She’s already part of it. Roosje of her own accord stays with the family who saved her life.

Martijn goes to live with his foster parents in a small working-class house in Amsterdam. Every day he cycles about twenty minutes to his public primary school, the Nicolaas Maess School.

“All that time there are only two Jewish boys in the class, one of which is me. It is after the war, the late 1940s, but nothing seems to have changed. Sometimes when the teacher is not there, the boys from the class hit me. They threw me down and sat on me. I am eleven years old and I feel very well: the hatred against us Jews continues. As if nothing had happened.”

Not long after, Martijn’s life takes a different turn. His foster parents ask him what he thinks about moving to Israel. Going by an alias, like many other Jews. “That saved me. Something had to change. And this was a great turning point for me. My whole life promised to be different. We left on 6 March 1950, after my Bar Mitzvah, which was also our farewell party. We said goodbye to friends and some family and left. I was thirteen years old and very happy to go.”

They settle in the coastal town of Nahariya.

Martijn attends secondary school and then studies electrical engineering at university. He enjoys the lessons and life in a society that is starting up. This period shapes him into who he has become, he says. He performs his military service and while still in the army, he marries Yaira. Martijn meets her when she returns a book to his house with a mutual friend. He immediately falls head over heels for her. Like him, Yaira survived the war.

After his military service, Martijn and Yaira settle in Jerusalem. He works as an engineer at the Hebrew University and becomes interested in projects in medicine and biology. So much so that he wants to get his master’s degree in Biophysics. The University of California at Berkeley gives him the chance and ensures that the young couple move to the United States in 1964. Martin is not yet thirty.

“Israel also became an important place for my sister Roosje. She visited me several times during the years I lived there. Then we would walk along the boulevard with my friends and I would see her perk up. We had discussions about life, about good and evil. Fifteen years after my foster parents and I emigrated, she did the same. She married and had three children. Finally, she too could start her future.”

At the same time, the restoration of rights was in full swing in the Netherlands during those years. From August 1945, the Council for the Restoration of Rights has been committed to returning property wrongly seized by the German occupier to its rightful owners. It is the legal procedure that for minor orphans, the court assigns an administrator to handle this. Martijn cannot remember how this went for Roosje and him. But he knows how it ended. In his personal archive, he has a statement from notary Drion from Breda with the division of their inheritance.

“My family’s houses were returned to me and Roosje after the war. Almost all houses and apartments went to Roosje, but the Mauritssingel 6-7 was for me. That house was a dream. We would all live there. I wanted to keep it and decided to rent it out. That this was taken from us before is bad, but not nearly as serious as what happened to my whole family. I still find it incomprehensible that only I, Roosje, an uncle and an aunt of the family were left. Why did this happen to us? And why did so many Dutch people join Hitler? In receiving the inheritance, I actually had proof that my family had been killed during the war. But believe it, I still didn’t. And accepting history happened much later.”

Martijn and Yaira have three children in the US: Daphne, Daniel and Ariel. After Berkeley, San Diego follows, where Martijn is doing his postgraduate. “Academia gives me a goal, a clear guideline, in my life. And with that many happy years. It made it clear to me what I do, and what I contribute to in life. It’s also a great environment to be in, very progressive. I have always had the pleasure of working with very nice people.”

“Now I’m retired, but I still go to my lab every day to research a cure for prostate cancer. I want to keep doing good, the morality of Judaism. In my case, that’s trying to make a lot of people better. That is what faith brought me.”

For most of his life, Martijn does not want to talk about the war. He can’t stand anyone bringing it up and wants nothing to do with it. Because it won’t bring his family back anyway. In the meantime, he has health problems that general practitioners cannot explain. Later it turns out that they are caused by a specific stress syndrome that Holocaust survivors in particular suffer from.

It was not until the nineties, when he was in his sixties, that he started his search. The reason for this is a call from the Red Cross in which the organization offers next of kin to find out the details of the death of family members. He registers and when Martijn receives the letter with the research result, he sees it for the first time: the dates of death and the extermination camps where they were murdered. Proof that his family is a victim of the Holocaust. In the years that follow, Martijn conducts follow-up research himself. He also travels to the Netherlands a few times for it. It is becoming increasingly clear how it all happened. But the acceptance is not there yet. The 2009 trial of John Demjanjuk, a camp guard at Sobibor Extermination Camp, changes that.

“That process has been very good for me. I was asked to be one of 22 accusers. This was a guard in the camp where my mother, sister, brother and aunt were killed. I didn’t have to think about it. I had to represent their voice, that’s how it felt.”

“During that process, I finally discovered the truth. The way the lawyers discussed the facts, so seriously, made me face it. It really happened. I just never could comprehend it before. During the process, I also met people who had experienced exactly the same thing and in whom I recognized a lot of myself. The trauma never goes away, but you can learn to forget it once in a while. To surround the feeling and not give up, but try to achieve something. Some are like brothers, we have that much in common. We still write to each other every New Year.”

“It is now history for me, but in some situations, it comes up again. After the trial, I also regularly went to the Netherlands. On my own, to do further research, but also with my children and grandchildren. I showed them everything: the Speelhuislaan with the wide sidewalk, the ‘dream house’ on the Mauritssingel with the spiral staircase that I never actually lived in myself. I had to sell it to buy a house for our family in San Diego. We also visited my grandparents’ tombstones at the Jewish cemetery in Oosterhout. Breda never had a Jewish cemetery itself. I wanted to show it to them all because it’s their history too. We all come from somewhere.”

Martijn will never live in the country where he was born. “Not everyone will agree with me, but there is no place for Jews in the Netherlands. The Jewish community there never really got the chance to grow. There is still anti-semitism. I have even heard such views from the grandson of the Hees family, the family that took me in at the risk of their own lives. Which he told in my presence. I can’t reach that with my head. He has never seen a Jew, except me. And he’s such a nice boy. After all these years I still don’t understand where this hatred against us comes from. I’m actually a nice person myself. I don’t get it, why?”

“My sister Roosje suffered a lot, a lot, more than I did in that respect. As a young Jewish girl, hiding among Catholics, she was often told that her people are evil and that she would have killed God. This had a major impact on her life. The doubt that this could be true has never gone away.”

sources

Four Freedoms

The Four Freedoms were goals articulated by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Monday, 6 January 1941. In an address known as the Four Freedoms speech (technically the 1941 State of the Union address), he proposed four fundamental freedoms that people “everywhere in the world” ought to enjoy:

“In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world.

The second is the freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear—which, translated into world terms, means a worldwide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbour—anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a world attainable in our time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.”

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, in support of FDR’s speech, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear—were first published on 20 February, 27 February, 6 March, and 13 March 1943.

sources

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/four-freedoms

The US and the Holocaust

Just to make it clear this post is not meant as an accusation or finger-pointing. I am forever grateful for what the US, and especially the US Army, did for my country. The outcome of World War II would have been more than likely—completely different—without the intervention of the US.

However, this doesn’t mean I shouldn’t highlight the mistakes made by the US when it comes to the Holocaust. There is this myth that the US didn’t know how bad the Nazis were. The US was told long before the war started, and even a few months before, they were drawn into it.

Otto Frank had requested a visa for the United States in 1938, which was denied. On 30 April 1941, Otto Frank sent a letter to his American friend Nathan Straus Jr. (whose friends called him “Charley”), the son of the founder of Macy’s department stores. The two men had met more than 30 years earlier, while Frank was in college in Heidelberg, and had become close friends.

April 30, 1941

Dear Charley,

…I am forced to look out for emigration and as far as I can see the U.S.A. is the only country we could go to. Perhaps you remember that we have two girls. It is for the sake of the children mainly that we have to care for. Our fate is of less importance. Two brothers of Edith emigrated last year and they work as ordinary workmen around Boston. Both of them earn money, but not enough to have us come.

They would be able to give an affidavit for their mother, living with us here, and they saved enough as, far as I can make out, to pay the passage for my mother-in-law…

In 1938 I filed an application in Rotterdam to emigrate to the U.S.A. but all the papers have been destroyed there…The dates of application are of no importance any longer, as everyone who has an effective affidavit from a member of his family and who can pay for his passage may leave. One says that no special difficulties shall be made from the part of the German Authorities. But in the case that an affidavit from family members is not available or not sufficient the consul asks for a bank deposit. How much he would ask in my case I don’t know. I am not allowed to go to Rotterdam and without an introduction, the consul would not even accept me. As far as I hear from other people it might be about $5,000. – for us four. You

are the only person I know that I can ask Would it be possible for you to give a deposit in my favor?”

The title of the post is taken from the Ken Burns documentary, a 3 part series. which explores the US response to the Nazi persecution of Jews, but, at six hours long, has enough room to extend its remit to other countries’ attitudes towards immigration and refugees (the UK is not spared). The first episode, The Golden Door, is bookended by both the Statue of Liberty and Anne Frank’s family. In 1934, the Franks fled Germany and moved to Amsterdam, along with hundreds of other Jewish families. Their intention was to reach the US. Coyote recounts solemnly that they found that “most Americans did not want to let them in”.

The miniseries begins in 1933, covering the national culture of the U.S. before World War II and the Holocaust, including topics such as antisemitism, racism, the eugenics movement and how Nazi Germany used Jim Crow laws in the American South as models for its own racial policy, including the Nuremberg Laws and other pieces of antisemitic legislation. Through interviews with Holocaust survivors, historians and witnesses, as well as through historical footage, the series examines the U.S. response to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Holocaust.

The documentary will be televised on BBC 4 on Monday, January 23.

Sources

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt20863280/?ref_=tt_ov_inf

https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust/personal-story/otto-frank

Sandy Hook Elementary School- 10 years ago.

On this day a deranged lunatic went into a elementary school and murdered 20 children and 6 staff members. I will not mention the killer because he doesn’t deserve our attention, He took the easy way out.

These are the names of the Sandy Hook elementary school mass murder.

Perpetrator’s mother:

Nancy Lanza, 52 (shot at home)

School personnel:

Rachel D’Avino, 29, behavior therapist

Dawn Hochsprung, 47, principal

Anne Marie Murphy, 52, special education teacher

Lauren Rousseau, 30, teacher

Mary Sherlach, 56, school psychologist

Victoria Leigh Soto, 27, teacher

Students:

Charlotte Bacon, 6

Daniel Barden, 7

Olivia Engel, 6

Josephine Gay, 7

Dylan Hockley, 6

Madeleine Hsu, 6

Catherine Hubbard, 6

Chase Kowalski, 7

Jesse Lewis, 6

Ana Márquez-Greene, 6

James Mattioli, 6

Grace McDonnell, 7

Emilie Parker, 6

Jack Pinto, 6

Noah Pozner, 6

Caroline Previdi, 6

Jessica Rekos, 6

Avielle Richman, 6

Benjamin Wheeler, 6

Allison Wyatt, 6

We can look for answers but we will never really find them. I am not going into the politics of this and the aftermath, because quite frankly both sides of the divide sicken me.

One fact is what needs to be remembered, all these kids would still be at school going age today, 10 years later.

sources

https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/newtown-marks-10-years-since-sandy-hook-tragedy/2935588/

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-63911172

https://www.britannica.com/event/Sandy-Hook-Elementary-School-shooting

Russians love their children too.

The song Russians has been going around in my head the last few weeks. Leaving aside the political message it is a beautiful song.

The melody was inspired by Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev’s Romance melody from the Lieutenant Kije Suite.

In 2010, Sting explained that the song was inspired by watching Soviet TV via inventor Ken Schaffer’s satellite receiver at Columbia University:

“I had a friend at university who invented a way to steal the satellite signal from Russian TV. We’d have a few beers and climb this tiny staircase to watch Russian television… At that time of night we’d only get children’s Russian television, like their ‘Sesame Street’. I was impressed with the care and attention they gave to their children’s programmes. I regret our current enemies haven’t got the same ethics.”

Sting’s bandmate , Police drummer Stewart Copeland . the son of a CIA operative had a very different outlook. But as Copeland explained, no matter how cogent his arguments, Sting could refute them with an indefensible lyric like “Russians love their children too.” Said Copeland, “You can’t argue with a poet.”

The lyrics have dated a small bit mainly because of the names of the political leaders. But if you change those names to the current leaders, which I will leave up to yourselves to do’ it is quite a current song that reflects the reality at the moment caused by the Ukraine Russia crisis.

“In Europe and America there’s a growing feeling of hysteria

Conditioned to respond to all the threats

In the rhetorical speeches of the Soviets

Mister Krushchev said, “We will bury you”

I don’t subscribe to this point of view

It’d be such an ignorant thing to do

If the Russians love their children too

How can I save my little boy from Oppenheimer’s deadly toy?

There is no monopoly on common sense

On either side of the political fence

We share the same biology, regardless of ideology

Believe me when I say to you

I hope the Russians love their children too

There is no historical precedent

To put the words in the mouth of the president?

There’s no such thing as a winnable war

It’s a lie we don’t believe anymore

Mister Reagan says, “We will protect you”

I don’t subscribe to this point of view

Believe me when I say to you

I hope the Russians love their children too

We share the same biology, regardless of ideology

But what might save us, me and you

Is if the Russians love their children too”

Sources

LyricFind

https://genius.com/Sting-russians-lyrics

You must be logged in to post a comment.