One of the most cruelest crimes committed by the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII, was the Bataan Death March.

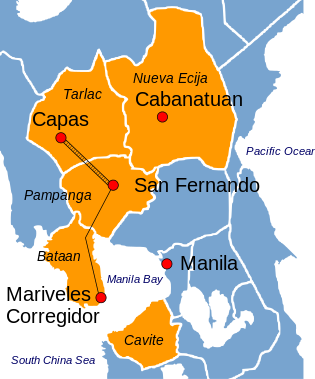

It was a march in the Philippines of some 66 miles (106 km) that 76,000 prisoners of war (66,000 Filipinos, 10,000 Americans) were forced to take, by the Japanese military to endure in April 1942, during the early stages of World War II.

After the April 9, 1942 U.S. surrender of the Bataan Peninsula on the main Philippine island of Luzon to the Japanese during World War II (1939-45), the approximately 76,000 Filipino and American troops on Bataan were forced to make the march to prison camps. Thousands were killed during the march. During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died. They were subjected to severe physical abuse, including beatings and torture. On the march, the “sun treatment” was a common form of torture. Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight without helmets or other head coverings.

It was like hell. But among all the evil and torture there was at least one moment of compassion.

Mario George Tonelli was born the son of Italian immigrants in the Chicago suburbs. He was a professional American football player who played running back for one season for the Chicago Cardinals.

He joined the Chicago Cardinals in 1940. However, feeling a sense of duty to serve his country, he decided to enlist in the Army at the end of the season. Reporting for duty at Camp Wallace, Texas, in March 1941, Tonelli remarked to a reporter that he would be able to use his Army training exercises as a football coach after he finished his service. In 1937 Tonelli played college football .

Tonelli spent three years with the Fighting Irish varsity, leading Notre Dame to the brink of a national championship in 1938. Following the College All-Star Game in 1939, he received his gold class ring, on the underside of which he had his initials and graduation date M.G.T. ’39engraved. He wore the ring proudly during a stint as an assistant coach at Providence College in 1939 and one season of pro football with the Chicago Cardinals in 1940..

On 7 December, 1941, the now SGT Tonelli was stationed at Clark Field on Luzon, the main island of the Philippines. The next day, as he exited the mess hall, a swarm of Japanese planes commenced bombardment of Clark Field. Unable to reach his anti-aircraft gun, he grabbed a nearby Springfield rifle and fired fruitlessly into the horde of enemy aircraft until the Japanese planes departed. Soon after the initial assault, Tonelli joined the rest of the American and Filipino forces in their withdrawal into the Bataan Peninsula.

For five months, Tonelli and his fellow soldiers fought valiantly against the Japanese juggernaut while their supply of food, medicine, and ammunition dwindled. On 9 April, 1942, the weak, starving, and exhausted American forces surrendered to the Japanese. On this day, Tonelli began his 1,236 day ordeal as a prisoner of the Japanese.

The following day, he found himself in what would become known as the Bataan Death March.

Fatigued by the months of fighting and his recent capture, Tonelli neglected to hide his gold Notre Dame ring, which he still wore proudly on his finger. A Japanese guard came by and pointed to the ring. Tonelli refused to hand his precious football memento over to the guard. Annoyed with his insolence, the Japanese soldier threatened to strike him. Tonelli finally decided to turn the ring over as a friend quietly warned him that no ring is worth dying for. As the guard left him, he knew he would never see his class ring again.

A few moments later a Japanese officer stepped up to Tonelli and asked in perfect English, “Did any of my men take anything from you?” Dazed and confused, he responded, “Yes, he took my Notre Dame ring.” The officer handed him his ring back and cautioned him to hide the ring so it would not be taken again. After a word of thanks from the grateful prisoner, the officer explained, “I was educated in America at the University of Southern California.” The officer stated that he knew about Tonelli’s game winning play against the Trojans in the final game of the 1937 season. “I know how much this ring means to you, so I wanted to get it back to you”

That little incident gave Tonelli the hope he needed to survive the rest of the war

Tonelli later buried the ring in a metal soap dish beneath his prison barracks to safekeep it from would be thieves.

sources

https://news.nd.edu/news/notre-dames-tonelli-faced-horrors-of-bataan-refused-to-die/

Mario Tonelli

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

Given the fact I am also a Dirk J(my J as in Johannes, the Dutch equivalent of John) I could not resist doing a piece on this man.

Given the fact I am also a Dirk J(my J as in Johannes, the Dutch equivalent of John) I could not resist doing a piece on this man.

You must be logged in to post a comment.