I am always surprised why so little is reported about the Holocaust in Luxembourg. In the late 1930s, Luxembourg had a population of approximately 300,000, of which 3.500 were Jews. In addition, more than 1,000 German-Jewish refugees had found shelter in Luxembourg.

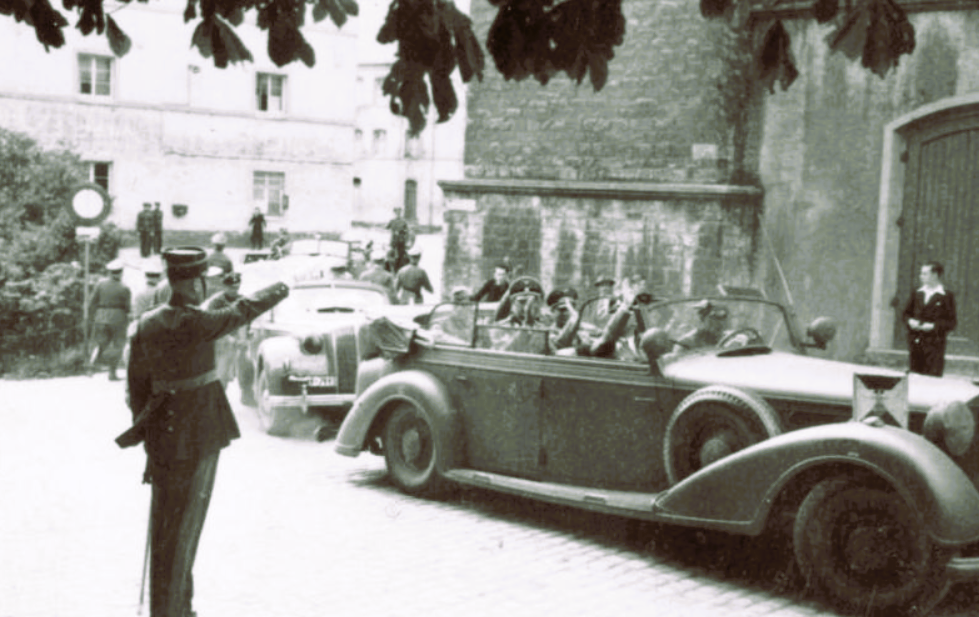

Nazi Germany occupied Luxembourg in May 1940, with the Luxembourg government fleeing into exile in London for the duration of World War II. Following a period of military administration, the country was placed under a German civil administration headed by Gustav Simon, district head of the adjoining German province of Koblenz-Trier.

In August 1942, Germany formally annexed Luxembourg.

On 6 August 1940, Simon ordered all police functions removed from the Luxembourg gendarmerie and entrusted to German police units. On 14 August, he proscribed references to the “State” or “Grand Duchy” of Luxembourg and suspended its constitution. On 26 August, the Reichsmark was introduced as legal tender, and on 20 January 1941, the Luxembourg franc was abolished. All existing political parties were banned, and the only authorized political institution was the Volksdeutsche Bewegung.

The Nuremberg Race Laws were introduced in Luxembourg on 5 September 1940, followed by several other anti-Jewish ordinances. In practice, however, Jews were encouraged to leave the country. Then, from the 8th of August 1940 until the Germans forbade emigration on 15 October 1941, more than 2,500 Jews left Luxembourg, the majority for the unoccupied zone of France. Many of these Jews were later deported from France to killing centers in occupied Poland.

The monastery of Cinqfontaines (Fünfbrunnen) was built in 1906 by the Catholic order of the Sacred Heart, and priests lived there continuously until 2021, apart from an interruption during the Second World War.

In 1941, the Nazi occupiers closed the monastery Cinqfontaines and reopened the site, called it the Jewish Retirement Home. It was a place of internment—by the Nazis—for the Jews still living in Luxembourg.

German authorities interned about 800 remaining Jews in the Fuenfbrunnen transit camp near the city of Ulflingen in Northern Luxembourg. Between October 1941 and April 1943, 674 Jews were deported from Fuenfbrunnen in eight transports to Lodz, Auschwitz, and Theresienstadt.

Like in all the other occupied countries—when, I say all, I mean in all Eastern European nations—there were people in Luxembourg who welcomed the Nazis. The Germanisation was facilitated by a collaborationist political group, the Volksdeutsche Bewegung (“Ethnic German Movement”).

From October 1941, Nazi authorities began to deport the around 800 remaining Jews from Luxembourg to Łódź Ghetto and the concentration camps at Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Only 36 Jews from Luxembourg are known to have survived the Nazi camps. Estimates of the total number of Luxembourg Jews murdered during the Holocaust range from 1,000 to 2,500. These figures include those killed in Nazi camps, in Luxembourg, or after deportation from France.

When Luxembourg was invaded and annexed by Nazi Germany in 1940, a national consciousness started to come about. From 1941 onwards, the first resistance groups, such as the Letzeburger Ro’de Lé’w or the PI-Men, were founded. Operating underground, they secretly worked against the German occupation, helping to bring political refugees and those trying to avoid being conscripted into the German forces across the border, and put out patriotic leaflets (often depicting Grand Duchess Charlotte) encouraging the population of Luxembourg to pull through. On 19 November 1944, 30 members of the Luxembourgish resistance defended the town of Vianden against the more extensive Waffen-SS attack in the Battle of Vianden.

On 27 January 2021, Luxembourg signed an agreement with the Jewish Consistory of Luxembourg (Consistoire Israélite de Luxembourg) on outstanding Holocaust asset issues. The signatories were the Prime Minister, Mr. Xavier Bettel, and the President of the Jewish Consistory, Mr. Albert Aflalo—while the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO) and the Luxembourg Foundation for the Remembrance of the Shoah acted as co-signatories.

They focused the agreement on a settlement for all outstanding Holocaust asset issues. In an interview with the prominent Luxembourg newspaper L’essentiel, the President of the Foundation for the Remembrance of the Shoah, Mr. François Moyse—referred to the chairmanship of IHRA, which Luxembourg held from March 2019 to March 2020 and which had considerably contributed to the dynamic of the negotiations. The negotiations had started soon after the country had taken over the presidency. The origins of this agreement dated back to 2009, when the United States, Luxembourg, and 45 other countries committed to rectify the consequences of the Nazi-era wrongful asset seizures and to promote the welfare of Holocaust survivors around the world by endorsing the Terezin Declaration.

Sources

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/luxembourg

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/luxembourg

[simple-payment id=”47270″

![kieffer-4[1]](https://dirkdeklein.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/kieffer-41.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.