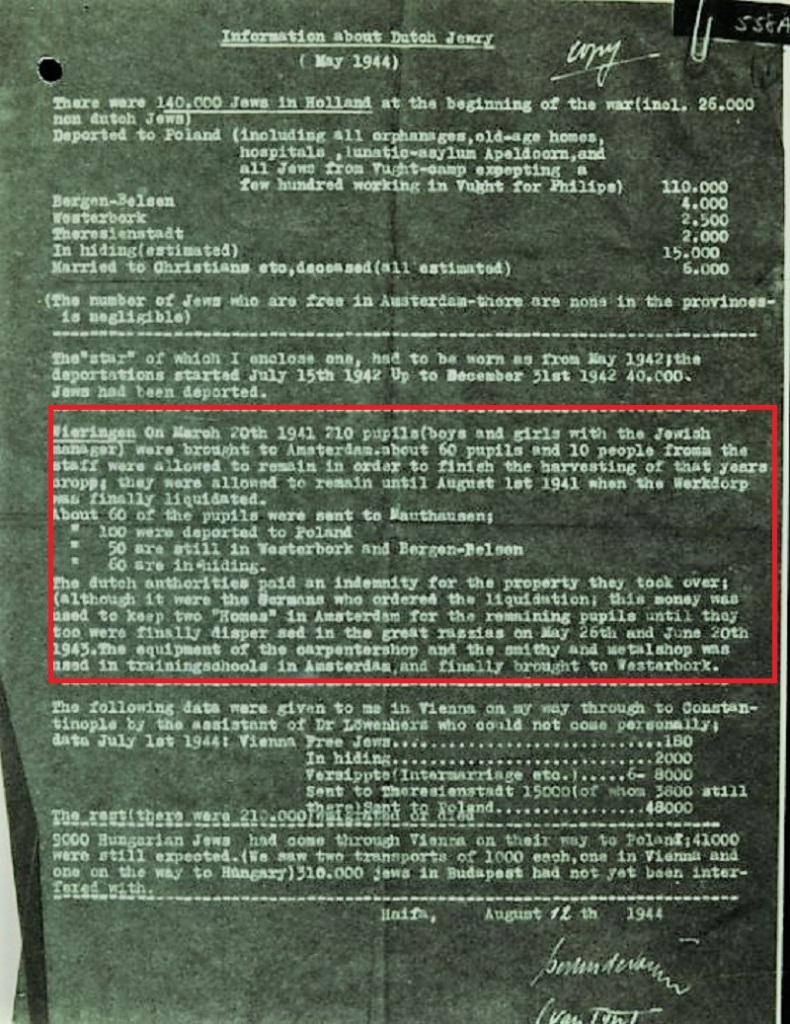

This is an element of the Holocaust which is often forgotten. There were dozens of Jewish labour camps in the Netherlands (as you can see, I did not say the occupied Netherlands).

On 7 January 1942, the Jewish Council in Amsterdam was put under pressure and made responsible for supplying 1,402 Jewish unemployed people. Ultimately, 1,075 unemployed people were identified, and more than 900 men gathered at the Amstel station on 10 January. They were sent to the labour camps in the Northern provinces, mainly to carry out reclamation work for the company Heidemij.

The Heidemij already led projects in the 1930s that employed the unemployed.

There was little work to be done in the first months. The ground was frozen and boredom set in. The men tried to break the routine by playing cards, writing a letter, taking a walk in the area or clearing snow. The worst part, however, was that the promised leave did not materialize. Hartog Italiaander wrote on March 4, 1942 from the De Beetse Labour Camp: “Leave has not yet been given, so I have already been away from home for six weeks. You understand that the mood here is becoming increasingly tense.”

After this first group, many more Jewish men from all parts of the country would follow. None were prepared for the conditions in the labour camps. The heavy work on the land was entirely unknown to most. The home front had to provide the necessary supplements (in the form of) clothing, money and food. This help also came from the immediate environment, sometimes not out of love for humanity but often out of profit.

At the beginning of 1942, the Nazis finally decided to deport and exterminate the Jews. The result was that in the spring and summer of 1942, conditions in the more than forty labour camps changed dramatically. The regime became stricter and was often based on German principles. Rations and wages were reduced, and leave and visits were limited. The letters were subject to censorship, and punishments were carried out more frequently.

The first deportations in July 1942 to Westerbork Camp (and then to Eastern Europe) increased uncertainty and fear among the Jewish forced labourers. Some volunteered for transport to Westerbork, afraid they might miss their relatives. Others fled. The vacant positions were filled with new workers who were often even less suitable (for the job).

On the night of the 2nd-3rd October 1942, most of the labour camps were surrounded by the Ordnungspolizei. The next morning, the Jewish forced labourers were taken to Westerbork on foot, by truck or by train under the guard of the same police.

Below are some stories of a few of those camps.

Conrad Camp

The first barracks on the Conrad Canal near Rouveen were built in the late 1920s. They were on the West side of the canal. In 1940, the barracks were moved to the East side. Unemployed people were given shelter in this camp and were used for land consolidation work.

Cook/manager Lonee had worked in Conrad since 1941. He was no stranger to labour camps, and he had already gained experience in camps in Rotterdam and Steenwijk.

Conrad was standing well outside the built-up area of Staphorst, just behind the old Rijksweg. The camp consisted of four residential barracks, each with eight rooms with six sleeping places, a barrack containing the manager’s house, office and kitchen. Furthermore, a canteen, some toilets, a warehouse and laundry rooms.

In the kitchen were three colossal cooking pots, approximately 1.5 metres in diameter. The cook/manager had help from a cook and domestic help from Staphorst. The men could play billiards in the canteen—with a stage.

In January 1942, the first Jewish forced labourers arrived at Camp Conrad. The largest group arrived in the camp in April 1942. Most came from Amsterdam, but men from the immediate area were also sent to Conrad. Manuel Roos, the representative, came from Staphorst. Bicycle repairer Salomon Brest and the brothers Jacob and Wolf Aronius, both manufacturers, came from neighbouring Zwartsluis. Wolf Aronius was the leader of the Jewish community in Zwartsluis. During the months they stayed at Conrad, they kept in touch with the people from their village. Every now and then—the butcher from Zwartsluit would cycle by, every now and then, and bring them sausages.

Loekie Halverstad from the Amsterdam Diamantbuurt wrote a letter to his friend Jan Tak on 10 May 1942:

“You may think that Loekie doesn’t speak up either. But here I am. That’s how it is. We don’t have much time for ourselves. I will give you the daily schedule here. Get up at 5 in the morning. In the cold! We have to be at work at 7 o’clock. Then we work until 9 o’clock. This work consists of loading sand onto tipping carts. Drive those carts a few hundred meters further and unload them there. And then back. We have to build a road. At 9 o’clock, we had a fifteen-minute break. Then we continue at once until 12 o’clock.

At a quarter to one, the stuff starts again until 3 o’clock and from a quarter past three to a quarter to 5. Then we go to camp. I have my bike here now, so I’ll be home at about 5 o’clock. Then I’ll wash and change clothes. I always wear shorts in the camp. I like that much better than plus-four. We have coffee at 6 o’clock and dinner at 7 o’clock. At half past eight I’m cutting bread for the next day and at 9 o’clock I’m in bed. Because if I don’t go to bed early, I’ll oversleep in the morning.

The food is tasty here, just very little. We should have much more for the work we do here. A bowl of porridge in the morning, which looks like starch, 6 sandwiches for the whole day and 1 plate of stew in the evening. Fortunately, I regularly get something from home, so I can endure it. The outside air has already given me a nice tan.

We also have a canteen here. There we can get, or rather, buy coffee, milk and ball bottles. There are also magazines. The first magazine I got my hands on was a bound volume of ‘We’ from 1938. And on the first page I opened were the photos of the May festival of the A.J.O. from Friesland. I also saw photos of the 20th anniversary in the Concertgebouw. That really did me good again.”

Isaac Arbeid arrived in Staphorst by train on Saturday afternoon, 2 April 1942, together with dozens of Jewish men from Amsterdam. From the station, they had to walk to Conrad Camp. For Arbeid, who worked illegally at the Paroolgroep, this was the first introduction to Staphorst/Rouveen. The reception was well prepared. The buildings were neat and bright. Room 13 was assigned to the Labour group. The first Sunday was a day off, and the Westerners noticed that this was a quiet day. The shops were closed, and the only people on the street were going to church.

At the end of April, a new group of 137 men arrived from Amsterdam. On 20 July, a small number from Drenthe had left Assen.

Bread and stew were often the daily fare in Conrad Camp. Also provided to the labourers was extra food done by planting potatoes between the barracks in April. At the Kruidhof shop/café on Oude Rijksweg 414, workers were allowed to stock up on all kinds of things. Kruidhof then asked in dialect whether they were from the Jewish camp. Then, for example, they would get the fruit for free. The store would be packed with Jewish people—wearing stars.

There was regular contact with the home front; people wrote letters almost daily. The delivery in both Amsterdam and the camp went smoothly. Sometimes, something tasty was sent, such as candy. Isaac Arbeid was allowed to telephone on Sundays with horse dealer Wicher Hofstede.

The men enjoyed reasonable freedom of movement and went to work without a German escort. In the evenings and on weekends, everyone could go wherever they wanted in the village.

From August 1942, the regime became stricter, and food became scarcer. Several changes were implemented. For example, at the beginning of the meal, it was no longer allowed to say, “Enjoy your meal,” but, “Good hunger.” From now on, people also had to march to the workplace, and stricter censorship was imposed on incoming mail.

Several men successfully attempted to escape from the camp. Jacob Aronius fled to Zwartsluis. There, he was arrested and transported to Amersfoort. He managed during the train journey to escape (again). He ultimately survived the war by going into hiding in Beilen.

Jaap van Abbe from Amsterdam also managed to escape from Conrad twice. The first time, he hid his belongings in the back of the toilet—so that he could take them with him during the escape. However, the plan was discovered. The second time, his father provided a bicycle to a farmer in Rouveen. There was also a false identity card. While working, Jaap managed to disappear. He went to Kampen by bike. He was terrified, especially during the inspection at the Kamperbrug. In Kampen, he spent a while with a resistance fighter. Later, he went into hiding in Amsterdam with his girlfriend’s father, where he experienced liberation.

On Friday, 2 October 1942, 10 to 15 men from the Grüne Polizei arrived at Camp Conrad. The workers in the camp were told that they were passing through and were staying overnight in Conrad because there was no room in Meppel. Some Jews became suspicious, and six men managed to escape that night. At 7 o’clock on Saturday, 3 October, the men were sent to camp Westerbork via Meppel.

After the departure of the Jewish forced labourers, Conrad Camp was given different destinations. During the war years, unemployed people from Rotterdam, evacuees from Zierikzee, passing German soldiers and evacuees from the coastal provinces lived in the barracks.

After the war, the NSB members were housed at the camp. Afterwards, the barracks were used for a while as an agricultural school, and Moluccans also lived there. The last resident, P. Nahumury, left on 28 July 1966, after the camp had been declared uninhabitable six months earlier. The last standing barrack at Conrad Camp was demolished in 2007 after being used as a church in Staphorst for a long time.

De Bruynhorst Castle

De Bruynhorst Castle was built in 1879 on the Lunterensekade in Ederveen. It is not known when it was established as accommodation for workers. Little is known about the castle as a Jewish labour camp. Only a letter and a postcard, written in early September 1942 by Josua Viool from Rotterdam, provide a limited picture of daily life in the camp. Every day, he had to walk 45 minutes to work, which consisted of shovelling sand “on an empty stomach.”

Josua wrote:

“Nothing may be sold to us. Do not send a package or receipts. They are being taken from us. If you want to send something to your father, send money. Life is extremely expensive. They all have plenty, but yes, every man for himself and God for us all.”

In a letter a short time later, Josua wrote that he had received two guilders in an incoming letter and immediately ran to the canteen to buy a few cups of coffee, cake and some fruit. This letter also states that the men had to clean the room after work performed, exercised for 45 minutes and could only go to bed after peeling potatoes.

On 3 October 1942, all men were transferred to Westerbork Camp, and most were sent to Auschwitz in the days and weeks that followed.

Palästina Labour Camp

On 3 September 1942, 139 Jews from Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague were taken to Camp Avegoor and later Palästina. Avegoor was the training centre of the Dutch SS—where Jewish forced labourers were put to work on the expansion of the complex.

Conditions were bad. Upon arrival, the men had to hand in clothing, food, money and securities. Instead, they were given thin clothes and clogs. The men were squeezed into the attic of the shuttered villa, “Irene,” on the Zutphensestraatweg near Ellecom.

Work had to be done at a breakneck pace for the groundwork for the construction of a sports field and a gymnastics hall. In the Avegoor Park, a narrow-gauge railway had been constructed to the underlying swamp, which had to be excavated. The working conditions were difficult, especially due to the brutality of the Dutch SS men who were training here. The forced labourers were constantly beaten with clubs.

The food was sufficient. In the morning, the men received one slice of bread. Those who, in the eyes of the guards, had not done enough work sometimes do not receive food for days. Malnutrition and exhaustion were the result.

After six weeks, 36 forced labourers had to be hospitalized. Three men would die in the camp or during the work.

The work was completed at the end of November 1942, and the forced labourers were sent to Westerbork camp. Here, they were admitted to the hospital on the orders of camp commander Gemmeker.

Philip Mechanicus wrote in his diary, “In Dépôt,” on May 31, 1943:

“The Ellecommers looked horrible. They had gone through a long period of torture. They were assured on behalf of the commander that they would not be sent to the East, but this assurance was ultimately violated and many were sent on.”

Sources

https://joodsewerkkampen.nl/overzicht-joodse-werkkampen

https://www.oorlogsbronnen.nl/bronnen?term=joodse+werkkampen

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.