Finishing up the ROCTOBER 2023 sessions with a Halloween special.

WORLD WAR II, MUSIC, HISTORY, HOLOCAUST

Finishing up the ROCTOBER 2023 sessions with a Halloween special.

A slightly different episode of Rocktober. Because Halloween is approaching rapidly, I thought it would be a good idea to have a look at some classic Rock tracks used in Horror Movies.

Dokken – Dream Warriors-Nightmare on Elm Street 3.

Motörhead – “Hellraiser” from Hellraiser 3: Hell on Earth

Fastway – “Trick or Treat” (from Trick or Treat)

Alice Cooper -Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives

Bonfire – Sword and Stone-Shocker.

Here are some World War II Halloween stories and images. The above image was published in the San Diego Union on 25 October 1942.

A Halloween Party in 1942

The excerpt below provides a wonderful example of how Halloween was celebrated in the USA during World War II:

“Write your Hallowe’en invitations on cutouts of black cats, cauldrons, scarecrows, pumpkins or witches. Use black or orange paper and write the invitation in the form of a jingle or just a note. Room decorations are a simple matter for they can be as casual as you like. Spread a few sheaves of corn around the room or stand up some stalks of corn amid a profusion of gay autumn leaves.

Orange or black candles or orange bulbs—just a few to create an eerie effect—can be used to provide the light. Large cutouts of black cats, witches, or pumpkins pinned to the walls around the room, brilliant orange, yellow, or red tablecloths of cotton or old sheets dyed in any of those colours enhance them for the party. Playing games that originate from the character of the occasion, like pulling fortunes from the witches’ cauldron or spirit rapping, are times of interest for this type of party.

And don’t forget that traditional cider and doughnuts, orange and black candies, ice cream moulds with a pumpkin, or made-with-honey pumpkin pie contribute much in a decorative way.” —Wartime Entertaining, Ethel X. Pator [Consolidated Book Publishers: Chicago] 1942 (p. 49).

(Note: the original Hallowe’en spelling)

Photo above: Children in Halloween costumes at High Point, Seattle, 1943. (Image courtesy of MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, pi23331.)

Topeka’s Edward “Smitty” Smith was embroiled in a bloody battle on 31st October 1944. He suffered two injuries on 31st October 1944 in Marieulles, France.

“At this point, you displayed great and courageous initiative by rushing forward and pointing out booby traps to enable members of your squad to proceed safely. Reaching the edge of a clearing you dashed into the clearing and emptied your rifle point-blank into the nearest enemy foxhole. You then ran behind a large tree, reloaded and repeated this action on a second enemy foxhole.

You returned and for the third time rushed an enemy position, throwing grenades in the foxholes. All this action was done under heavy enemy small arm and machine-gun fire and returning from your third gallant raid you were seriously wounded in the left arm by enemy rifle fire. You then jumped into a foxhole for cover, setting off a booby trap, which wounded you the second time (in the left leg). But even after this second wound, it was only at your squad leader’s order that you went to the rear.

Major General Harry Twaddle – Commanding General of 95th Division.”

After his Halloween adventures, Smith received a Purple Heart, Combat Medal, Victory Medal, and European Campaign Medal.

The Belfast Telegraph published the following article on Halloween celebrations on 31st October 1940.

“Halloween will be celebrated in the traditional manner this evening with parties, dances, and other forms of entertainment notwithstanding the changes and difficulties brought by the war.

From the kiddies’ point of view, however, the evening will lack that sparkle and excitement, which fireworks and bonfires give to the scene and which, of course, are things of the past in these days of the blackout.

…

The scarcity of sugar will have its effect on the baking of cakes, but judging by the demand for threepenny bits this morning, the old-fashioned apple tart will still have its fascination for youthful ‘treasure hunters’.”

Halloween and Bonfire Night 1940 by Neil Coleman

“We were Church of England, my cousin Geoffrey and me, and were members of the choir at St Michael’s and All Angels, on Melton Road on that piece of land that lay between Moira Street and Cannon Street just North of the Melton turn in Belgrave, Leicester. We lived in a large house on a terrace directly opposite a church. We were both pupils at St Patrick’s Roman Catholic school on Harrison Road, Geoff being nine and I was eight which meant that we were in different years. The school was connected with the Church of Our Lady at the Harrison Road end of Moira Street. And in 1940 at Halloween, we went to the party given in the hall attached to the church. Run by the teachers and parents there was apple-bobbing, lucky dips in bran-barrels, toffee apples, ginger-snaps, and all sorts of games and fun. My mother went with us and there was an enormous Moon on what was a clear night. Walking back along Moira Street, Mother said she thought the Moon was what she thought was called a ‘Hunter’s Moon.’

That night was 31st October 1940.”

Sources

https://www.beaumontenterprise.com/news/article/Halloween-tricks-not-a-treat-during-WWII-4932055.php

https://www.enemyinmirror.com/halloween-1942/

Many people think that Halloween is a festival of evil, where the aim is to scare people by dressing up in very scary costumes, or what I find more bizarre is the whole “trick or treat” notion. Everyday we tell our kids not to take sweets or candies from strangers, come 31 October we turn the world upside down and say “Go out children, fear not and go to those stranger’s houses and ask them for treats”

However that is not what Halloween is really about.

Halloween originated with the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, when people would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off ghosts. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as a time to honor all saints. Soon, All Saints Day incorporated some of the traditions of Samhain. The evening before was known as All Hallows Eve, and later Halloween. Over time, Halloween evolved into a day of activities like trick-or-treating, carving jack-o-lanterns, festive gatherings, donning costumes and eating treats.

Samain or Samuin was the name of the festival (feis) marking the beginning of winter in Gaelic Ireland. It is attested in the earliest Old Irish literature, which dates from the 10th century onward.

Samhain had three distinct elements. Firstly, it was an important fire festival, celebrated over the evening of 31 October and throughout the following day.

To commemorate the event, Druids built huge sacred bonfires, where the people gathered to burn crops and animals as sacrifices to the Celtic deities. During the celebration, the Celts wore costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins, and attempted to tell each other’s fortunes. The flames of old fires had to be extinguished and ceremonially re-lit by druids.

It was also a festival not unlike the modern New Year’s Day in that it carried the notion of casting out the old and moving into the new.

To our pagan ancestors it marked the end of the pastoral cycle – a time when all the crops would have been gathered and placed in storage for the long winter ahead and when livestock would be brought in from the fields and selected for slaughter or breeding.

But it was also, as the last day of the year, the time when the souls of the departed would return to their former homes and when potentially malevolent spirits were released from the Otherworld and were visible to mankind.

In addition to causing trouble and damaging crops, Celts thought that the presence of the otherworldly spirits made it easier for the Druids, or Celtic priests, to make predictions about the future. For a people entirely dependent on the volatile natural world, these prophecies were an important source of comfort during the long, dark winter.

The early pagan holiday of Samhain involved a lot of ritualistic ceremonies to connect to spirits, as the Celts were polytheistic. While there isn’t a lot of detail known about these celebrations, many believe the Celts celebrated in costume ,basically , they were likely as simple as animal hides, as a disguise against ghosts, enjoyed special feasts, and made lanterns by hollowing out gourds.

The Celts also set out gifts of food, hoping to win the favor of the spirits of those who had died in the past year. They also disguised themselves so the spirits of the dead wouldn’t recognize them.

By the 9th century, the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it gradually blended with and supplanted older Celtic rites. In 1000 A.D., the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to honor the dead. It’s widely believed today that the church was attempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related, church-sanctioned holiday. Over time, as Christianity took over and the pagan undertones of the holiday were lessened, the basic traditions of the holiday remained a part of pop culture every year; they simply evolved and modernized.

The word Halloween or Hallowe’en dates to about 1745 and is of Christian origin. The word Hallowe’en means “Saints’ evening”. It comes from a Gaelic term for All Hallows’ Eve (the evening before All Hallows’ Day).

There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween. Some of these games originated as divination rituals or ways of foretelling one’s future, especially regarding death, marriage and children. During the Middle Ages, these rituals were done by a “rare few” in rural communities as they were considered to be “deadly serious” practices. In recent centuries, these divination games have been “a common feature of the household festivities” in Ireland and Britain. They often involve apples and hazelnuts. In Celtic mythology, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld and immortality, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom. Some also suggest that they derive from Roman practices in celebration of Pomona.

The following activities were a common feature of Halloween in Ireland and Britain during the 17th–20th centuries. Some have become more widespread and continue to be popular today. One common game is apple bobbing or dunking , in which apples float in a tub or a large basin of water and the participants must use only their teeth to remove an apple from the basin. A variant of dunking involves kneeling on a chair, holding a fork between the teeth and trying to drive the fork into an apple. Another common game involves hanging up treacle or syrup-coated scones by strings; these must be eaten without using hands while they remain attached to the string, an activity that inevitably leads to a sticky face. Another once-popular game involves hanging a small wooden rod from the ceiling at head height, with a lit candle on one end and an apple hanging from the other. The rod is spun round and everyone takes turns to try to catch the apple with their teeth.

Many people were said to dress up as saints and recite songs or verses door to door. Children would also go door to door asking for “soul cakes,” a treat similar to biscuits. Technical note: Soul cakes originated as part of the All Souls’ Day holiday on November 2 , but eventually became a part of Halloween night as the concept evolved into trick-or-treating. The candy-grabbing concept also became mainstream in the U.S. in the early to mid-1900s, during which families would provide treats to children in hopes that they would be immune to any holiday pranks.

How trick-or-treating became a tradition

But how did those Celtic traditions evolve into one of children trick-or-treating in costumes for fun and candy—not for safety from spirits?

According to the fifth edition of Holiday Symbols and Customs, in as early as the 16th century, it was customary in England for those who were poor to go begging on All Souls’ Day, and children eventually took over the custom. At the time, it was popular to give children cakes with crosses on top called “soul cakes” in exchange for prayers on your behalf.

Lisa Morton, author of Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween, traced one of the earliest mentions of typical Halloween celebrations to a letter from Queen Victoria about spending Halloween around a bonfire in Scotland in 1869.

“Having made the circuit of the Castle,” the letter said, “the remainder of the torches were thrown in a pile at the south-west corner, thus forming a large bonfire, which was speedily augmented with other combustibles until it formed a burning mass of huge proportions, round which dancing was spiritedly carried on.”

Morton writes that people in the American middle class often were anxious to imitate their British cousins, which would explain a short story printed in 1870 that painted Halloween as an English holiday celebrated by children with fortune-telling and games to win treats.

However, Morton writes that it’s possible that trick-or-treating may be a more recent tradition that, surprisingly, may have been inspired by Christmas.

A popular 18th- and 19th-century Christmas custom called belsnickling in the eastern areas of the U.S. and Canada was similar to trick-or-treating: Groups of costumed participants would go from house to house to perform small tricks in exchange for food and drink. Some belsnicklers even deliberately frightened young children at houses before asking if they had been good enough to earn a treat. And other early descriptions say that those handing out treats had to guess the identities of the disguised revelers, giving food to anyone they couldn’t identify.

In the 19th century, “tricks”—such as rattling windows and tying doors shut—were often made to look as though supernatural forces had conjured them. Some people offered candy as a way to protect their homes from pranksters, who might wreak havoc by disassembling farm equipment and reassembling it on a rooftop. By the early 20th century, some property owners had even begun to fight back and lawmakers encouraged communities to keep children in check with wholesome fun.

These pranks likely gave rise to the use of the phrase “trick-or-treat.” Barry Popik, an etymologist, traced the earliest usage of the phrase in connection with Halloween to a 1927 Alberta newspaper article reporting on pranksters demanding “trick or treat” at houses.

So you see there is a lot more to Halloween then just getting dressed up, trick or treating or Jamie Lee Curtis being chased by Michael Myers.

sources

https://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/origin-of-Halloween.html

https://www.countryliving.com/entertaining/a40250/heres-why-we-really-celebrate-halloween/

https://www.history.com/topics/halloween/history-of-halloween

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halloween

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samhain

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

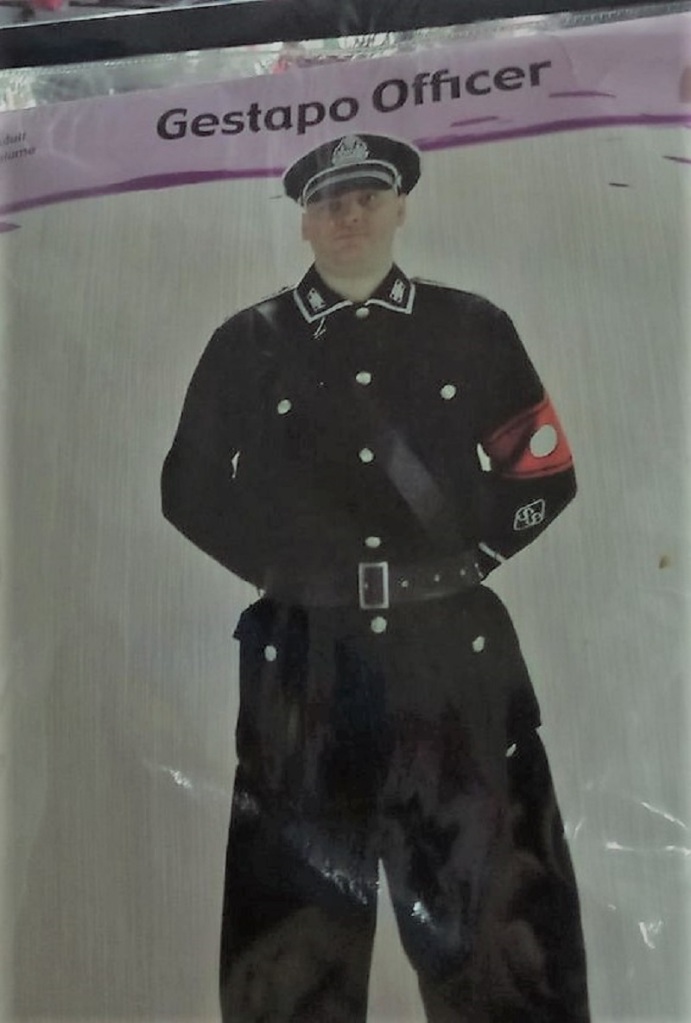

I was on Irish National radio this afternoon, discussing the sale of Nazi uniforms as Halloween costumes in Ireland.

It was on Joe Duffy’s Liveline show. I enjoyed being on it, but the show was a bit manipulated. I received a call from one of the researchers at 10 a.m. this morning. He asked me my opinion about the sale of Nazi costumes for Halloween. I told him in principle, I was against it. The researcher let me know that the show had been approached (by an anonymous lady) who had seen the costumes. Then he sent me a link.

I replied to his email.

Hi D,

Sorry, I missed your call.

The outfits are offensive. If you allow this then you also have to allow KKK, Black and Tan, Paedophile Priest outfits, and Jimmy Saville costumes, etc. To put it in context, the Nazis murdered 17 million between 1933 and 1945, of which 6 million were Jews, but also people from the LGBT community and people with disabilities.

I wonder if the people who wear these outfits ever consider that.

The horrors of the Nazi regime lived on in the minds of many Europeans long after the war, and still today for some.

My grandfather was killed by Nazis, as were some cousins of my mother.

Aside from that, it has nothing to do with Halloween.

I was then called again and was advised that when I talk to the presenter, I should pretend I found this on social media.

When the interview started—it was implied that I had contacted the show and not the other way around. I can understand why they did that, but it was a bit bizarre.

But have a listen for yourself.

https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22023230/

Most people think that Halloween is a festival of evil, where the aim is to scare people by dressing up in very scary costumes, or what I find more bizarre is the whole “trick or treat” notion. Everyday we tell our kids not to take sweets or candies from strangers, come 31 October we turn the world upside down and say “Go out children,fear not and go to those strangers houses and ask them for treats”

On the other hand there are people who think is is the time when Jamie Lee Curtis gets chased by that masked knife wielding psychopath Michael Myers.

In fact Halloween could not be further removed from either of the aforementioned. It goes back for approximately 2000 years.

To find the origin of Halloween, you have to look to the festival of Samhain in Ireland’s Celtic past.

Samhain had three distinct elements. Firstly, it was an important fire festival, celebrated over the evening of 31 October and throughout the following day.

The flames of old fires had to be extinguished and ceremonially re-lit by druids.

It was also a festival not unlike the modern New Year’s Day in that it carried the notion of casting out the old and moving into the new.

To our pagan ancestors it marked the end of the pastoral cycle – a time when all the crops would have been gathered and placed in storage for the long winter ahead and when livestock would be brought in from the fields and selected for slaughter or breeding.

But it was also, as the last day of the year, the time when the souls of the departed would return to their former homes and when potentially malevolent spirits were released from the Otherworld and were visible to mankind.

The Celts celebrated four major festivals each year. None of them was connected in anyway to the sun’s cycle. The origin of Halloween lies in the Celt’s Autumn festival which was held on the first day of the 11th month, the month known as November in English but as Samhainin Irish.

This day marked the end of summer and the harvest and the beginning of the dark, cold winter, a time of year that was often associated with human death. Celts believed that on the night before the new year, the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead became blurred. On the night of October 31 they celebrated Samhain, when it was believed that the ghosts of the dead returned to earth.

In addition to causing trouble and damaging crops, Celts thought that the presence of the otherworldly spirits made it easier for the Druids, or Celtic priests, to make predictions about the future. For a people entirely dependent on the volatile natural world, these prophecies were an important source of comfort and direction during the long, dark winter.

To commemorate the event, Druids built huge sacred bonfires, where the people gathered to burn crops and animals as sacrifices to the Celtic deities.

During the celebration, the Celts wore costumes, typically consisting of animal heads and skins, and attempted to tell each other’s fortunes.

On May 13, 609 A.D., Pope Boniface IV dedicated the Pantheon in Rome in honor of all Christian martyrs, and the Catholic feast of All Martyrs Day was established in the Western church. Pope Gregory III later expanded the festival to include all saints as well as all martyrs, and moved the observance from May 13 to November 1.

By the 9th century the influence of Christianity had spread into Celtic lands, where it gradually blended with and supplanted the older Celtic rites. In 1000 A.D., the church would make November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to honor the dead. It’s widely believed today that the church was attempting to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related church-sanctioned holiday.

All Souls Day was celebrated similarly to Samhain, with big bonfires, parades, and dressing up in costumes as saints, angels and devils. The All Saints Day celebration was also called All-hallows or All-hallowmas (from Middle English Alholowmesse meaning All Saints’ Day) and the night before it, the traditional night of Samhain in the Celtic religion, began to be called All-Hallows Eve and, eventually, Halloween.

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

I know I am a day early but with all the trick or treaters calling tomorrow I might not be have the time to do a piece then.

Although Halloween is originally a Celtic event.Halloween’s origins date back to the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-in). The Celts, who lived 2,000 years ago in the area that is now Ireland. I will be looking at the WWII celebrations of Halloween from an American perspective.. Below are pictures and posters of Halloween during the Second World War. However I am starting of with a picture from before WWII, in fact it is a picture of Halloween 1918, 11 days before the end of WWI. The reason why I am posting this picture is because of the use of the Swastika,long before the Nazi’s stole it.

1942 propaganda poster.

1944

Horror movies were still being made during the war these are posters from “the Uninvited” which was released a few weeks before Halloween 1944.

Children in Halloween Costumes at High Point, Seattle, 1943

Japanese American group of evacuees in Halloween costumes and make-up at the Harvest Festival on October 31, 1942 at the Tule Lake Relocation Center in California.

Coca-Cola Halloween poster 1944

4th November 1942: A GI and his girl friend dancing at a Halloween party for US soldiers in London during WW II.

I suppose it was easier to face horrors of Halloween then the real horrors of World War II.

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.