Category Archives: Geleen

Rory Gallagher—One of my Few Regrets

My Fellow Citizens—The Jews from Geleen

I want to start by saying that I am not Jewish, although I may have some Jewish ancestry. I am still looking into that. However, the Jews from Geleen were my fellow citizens, as were any other one, regardless of race or colour were my fellow citizens.

However, the majority of the Jews of Geleen were murdered during the Holocaust—this was not the case for other groups. The picture above is of a plague which was placed on the wall of the town hall on August 25, 2012, to commemorate a group of 20 Jews who were deported from that spot 70 years earlier, on August 25, 1942.

The text translates to:

FROM THIS PLACE, IT WAS ON

AUGUST 25, 1942 A LARGE

GROUP OF FELLOW JEWISH CITIZENS

WERE. DEPORTED FROM GELEEN

MAY THEIR SOULS BE INCLUDED IN THE BUNDLE OF ETERNAL LIFE

Following is the story of one of my fellow Jewish citizens from Geleen and her family.

Ilse Roer

Father Max Roer, born in 1886, was a butcher (Metzgermeister) in Zülpich in the Eifel. He married Jennie Baum from Bauchem in 1920 in Geilenkirchen. Helene (Leni) was born in 1921, and her sister Ilse in 1925. Max Roer died in Zülpich in 1932.

Two of Ilse‘s mother’s half-brothers, Max and Karl Baum, settled in Geleen on the Bloemenmarkt ( Flower Market) in May 1937, followed a month later by Jennie Roer-Baum and the teenagers Leni and Ilse. Ilse’s aunt Henriette Moses-Baum had already settled in Geleen with her family in 1934, and her other sister Johanna Gottschalk-Baum, with her family, emigrated to Valkenburg in 1938. Max and Karl’s two brothers, Bernhard and Albert, emigrated to America in 1938.

The Baum family took over the Gijzen butcher shop on the Bloemenmarkt, located there since 1929. Shortly after arriving in Geleen, Max, Karl, and Jennie opened their beef, pork and lamb butchery as partners on May 15, 1937, under the trade name Gebr. Baum, register with the Chamber of Commerce in Heerlen.

On January 2, 1939, the Baum grandparents registered at the Bloemenmarkt. Grandpa Samuel died a few months after the outbreak of war, on October 11, 1940, aged 78. He and Grandma Sophie then lived in Burg. Lemmensstraat 225. After his death, Grandma moved in with her children at the Bloemenmarkt. Uncle Max married Gerta Kaufmann from Waldenrath in 1941, who also moved into the Flower Market then.

Leni and Ilse Roer were part of the first group of Jews who were transported via Maastricht to Westerbork camp and from there to Auschwitz under the guise of ‘Arbeitseinsatz’ on August 25, 1942. Leni was gassed there upon arrival. Ilse was initially spared by being employed as a tailor. She died on October 2, 1942, on the “Kasernenstraße” in Auschwitz, according to the Auschwitz death register of influenza.

I lived on the Burg Lemmensstraat 141. The Bloemenmarktt is the small shopping centre in the part of Geleen called Lindenheuvel. All of this is in minutes of waking distance from where I grew up. That is how close and tangible the Holocaust still is.

Sources

https://www.stolpersteinesittardgeleen.nl/Slachtoffers/Ilse-Roer

https://www.tracesofwar.nl/sights/136569/Plaquette-Gedeporteerde-Joden-Geleen.htm

https://www.4en5mei.nl/oorlogsmonumenten/zoeken/4241/geleen-plaquette-voor-gedeporteerde-joden

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

The Residents of Peschstraat 28, Geleen—All Murdered

Holocaust in the “Westelijke Mijnstreek”

Before I go into the main story I have to explain the geographical history of the Westelijke Mijnstreek (Western Mining area). It is situated in the province of Limburg, the most southern province of the Netherlands, in the southeast of the country. It is also the nearest to Germany, in many cases literally a walking distance away from Germany. Why this is important will become clear later on. The Westelijke Mijnstreek was a mining area until 1968. Until 2001 the 2 main principle municipalities were Geleen and Sittard, in January 2001 the 2 towns merged into one bigger city carrying the name Sittard-Geleen. The Westelijke Mijnstreek is also the start of Zuid Limburg or South Limburg. Contradictory to popular belief, the Netherlands isn’t completely flat. The hills in Zuid Limburg, often referred to as the heuvelland, or hill land are formed by the foothills of the Belgian Ardennes and the German Eifel.

This geographical bit of history is important to understand the wider context of the main story. Herman van Rens, a retired General Physician from the Westelijke Mijnstreek, became a Holocaust researcher, and in his research, he discovered that more Jews survived the Holocaust in Limburg, than in the rest of the Netherlands, Approximately 50 % of Jews in Limburg survived, whereas nationally it was only 25%. This is remarkable because of the close proximity to Germany, as stated earlier often only walking a distance away.

However, this also means that 50% of Limburg Jews did not survive the Holocaust. Following are a few stories of those who were murdered.

The picture at the start of the blog is of the Croonenberg Family of Grevenbicht, a small village near Sittard.

The Croonenberg family had lived in Grevenbicht for at least 200 years. By profession they had always been butchers and cattle traders. The Zeligman family had lived in Meerssen for several generations, but mother Helena had spent half her childhood in Sittard. Grandmother Julia Falkenstein, after whom Julienne was named, came from Gangelt.

Erna and Julienne were the only Jewish children in Grevenbicht. They had their grandfather Gustaf and great-uncle Karel Croonenberg living in the house, and there were no other Jews in the village. They therefore went to the Catholic Sisters’ Preschool in Grevenbicht at the age of three and to the Maria School from the age of six and mainly had friends in the village. They met Jewish children and adults in Sittard, on Saturdays in the synagogue and on Sundays at Rabbi Van Blijdestein’s religion class. Their grandmother uncle and aunt Zeligman also lived in Sittard and the related Sassen-Falkenstein family.

Sittard had a flourishing Jewish community for centuries, with a synagogue in Molenbeekstraat and later Plakstraat, and its own cemetery at Fort Sanderbout and later on the Dominicanenwal. From time to time there were frictions and incidents between the Catholic majority and the Jewish minority, but generally, they lived together in good harmony.

From 1941 onwards, the freedom of movement of Jews became increasingly restricted: they were no longer allowed to go to cinemas, libraries, swimming pools, parks or catering establishments, and were no longer allowed to be members of non-Jewish associations; From September 1941, Erna and Julienne were no longer allowed to go to school in Grevenbicht. An improvised Jewish school was set up in Sittard, but the question is how often the girls from Grevenbicht attended it.

At the end of August 1942, the call came for Arthur and his family to report for ’employment in Germany’. Early one morning they were taken in a truck to Sittard, and from there by train together with many other Jewish families to Maastricht for registration and control, the next day to Camp Westerbork and a few days later from there by train to Auschwitz. Arthur was among the men who had to leave the train at the Kosel labor camp, about 80 kilometers before Auschwitz. These men were put to work in various camps from Kosel.

Helena and the girls were gassed immediately after arriving in Auschwitz on August 30 or 31, 1942, less than a week after their departure from Grevenbicht. Grandpa Gustaf remained alone in the house until he too was deported in April 1943. None of the family survived, except some of Arthur’s great-uncles and aunts and a cousin of Helena.

A party in Sittard in 1941 or 1942; a pleasant get-together, children playing in the street. Nothing special you might say, except that it was captured on film. However, appearances are deceiving, because the film bears witness to daily Jewish life in the Westelijke Mijnstreek, especially in a period that was becoming increasingly dark and threatening. We see how Isaac Wolff celebrates his Bar Mitzvah at home in the Landweringstraat in Ophoven Dozens of family members and Rabbi Van Bledenstein and his wife are guests and participate in the festive meal, adorned with paper hats.

Isaac Wolff was deported to Auschwitz in June 1943 from Vught via Westerbork on the so-called children’s transport. He was 14 years old when he was murdered on 3 September 1943.

Isaac’s father was Herman Wolff.

Herman Wolff was the only child of shopkeeper Isaac Wolff from Boxmeer and Sophia Silbernberg from Sittard. He grew up in Ophoven at Dorpsstraat 28 and became a tailor. In 1926 he left for Amsterdam with his parents, where he married Rozette in August 1927. They then settled in Sittard at Landweringstraat 4 (later renumbered to 15) and had two sons, Isaac and Bennie.

Herman became manager and owner of the local tricotage factory ‘Weta’ (Weverij En Tricotage Atelier), located at Landweringstraat 17b, next to their house. He founded this company in January 1935 together with partner Joseph Saile from Rottenburg (Württemberg). Saile was a weaver by profession and lived at Kruisstraat 13 as a boarder with the widow Zeligman from 1933 until his marriage in 1940. In November 1941, Herman had to resign and the occupiers placed Weta under an ‘Aryan’ administrator. Saile had to join the Wehrmacht in early 1942.

In the autumn of 1941, the Wolff family’s Bar Mitzvah of eldest son Ies was captured on film, a unique time document, where many family members and other Sittard Jews were guests in their home (see the video). This is the only known footage of the Wolff family.

A year later, almost the entire community was deported. Herman and his family had been given a reprieve because he was chairman of the Jewish Council in Sittard, but in April 1943 they too had to be transported to Vught. In June 1943, Rozette and the children continued on to Westerbork on the so-called children’s transport, from where they were deported to Auschwitz and murdered at the end of August. Herman also had to board the train to Auschwitz on November 15, 1943 and died on an unspecified date in Auschwitz or the surrounding area.

Seven other people had lived with the family, who, in addition to the (‘half-Jewish’) maid, were also deported: in February 1941 the widow Stein-Salomon and her eldest daughter came to live with them, in November 1942 the Schwarz-Wihl couple, and in February 1943, Rozette’s parents. None of them survived.

The story of Albert and Ida (Ajga) Claessens

Due to the flexible local admission policy in the early 1930s, Amby, in Maastricht counted many Jewish refugees from Germany and Eastern Europe, already over a hundred in 1933. In Zawiercie, where about a quarter of the population was Jewish, there had been pogroms in 1919 and 1921; It is possible that the Krzanowska family already fled their country to Germany at that time. Ida had arrived in Amby from Aachen in October 1936. She lived there on Hoofdstraat. Her brother Herman had also settled in Amby with his family, and her sister Rachella married another refugee there in 1934. They wrote their family name themselves as Chrzanowski. Herman was a wedding witness at Ida’s wedding to Albert Claessens on April 4, 1938, in Amby. Albert worked at the coking factory in Geleen.

The young couple settled in Geleen at Pastoor Vonckenstraat 51.

By order of the Reich Commissioner, Albert was fired from the State Mines on April 1, 1941. He later earned a living as a ground worker.

Albert did not think about going into hiding; he assumed that the Jews were taken to labor camps in Germany. At the first call, on August 25, 1942, he and Ida, together with many others, were taken via Maastricht to Westerbork, where they arrived on August 26. From there they were deported to Auschwitz on August 28. On August 25, 1942, the Geleen police report stated that all perishable goods had been removed from their house.

Ida Claessens-Krzanowska and Cilly Claessens-Hirsch were gassed immediately after their arrival in Auschwitz, less than a week after their departure from Geleen. Albert and Jozef were among the men who had to leave the train at the Kosel labor camp, about 80 kilometers before Auschwitz. These men were put to work in various camps from Kosel. Nothing further is known of their fate; only the note ‘died in Central Europe’ testifies to their sad fate.

Brother Herman Chrzanowski appears to have gone into hiding with his wife and two children and survived the war, as did sister Rachella and her husband.

sources

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/123055/isaac-wolff

https://www.stolpersteinesittardgeleen.nl/Stichting

https://historiesittardgeleenborn.nl/verhaal/14/holocaust-in-de-westelijke-mijnstreek

https://halloonline.nl/verhalen/bericht/herman-van-rens-houdt-de-holocaust-onder-de-aandacht

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

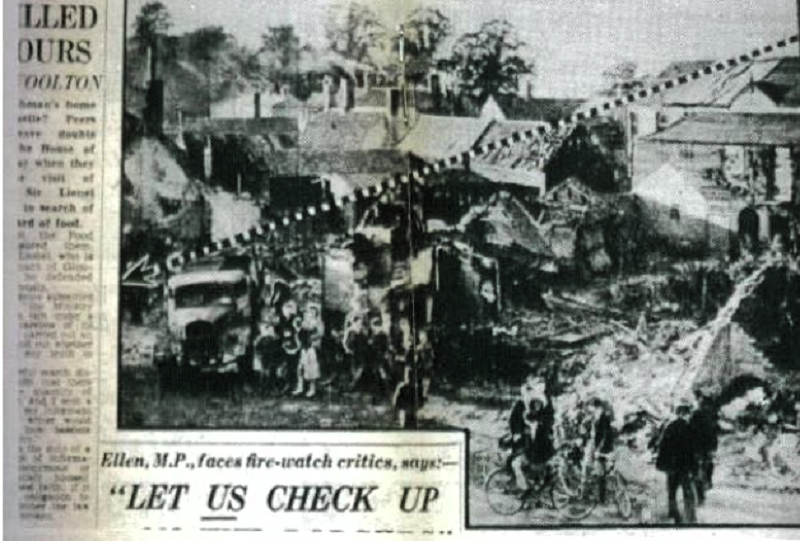

The Bombing of Geleen—5 October 1942

I have written about the bombing of Geleen before, but since today is the 81st anniversary, I thought it a good idea to revisit that awful day. Geleen is a town in the southeast part of the Netherlands. It used to be a mining town.

Although the Bombing of Geleen was a devastating event, I only learned about it a few years ago.

On 5 October 1942, the British RAF accidentally bombed a considerable part of South Limburg, particularly Geleen. As a result, 83 residents died, and many were injured. The material damage was immense. Due to the bad weather, the British had dropped their explosive load randomly over a far too large area.

On Monday evening, 5 October 1942, a total of 257 bombers took off in quick succession from various airfields in England. All aircraft were from the Royal Air Force (RAF). The crews consisted mainly of English and Canadians. The bombers were of the Wellington, Stirling, and Lancaster types. It was important that the weather forecast for the bombing flight (focused on destroying the German city of Aachen) cooperated. The expectation was that rain and low clouds would occur up to the northern German coastal area. A thunderstorm front over western France and southern England would also cause cloud cover above the Aachen target area. A cold front would cause difficulties in the area around Aachen. The bombers took off from the airfields with a formation over the Channel onto a Southern approach route—flying over the French town of Le Crotoy. However, to the North were the German air defenses—thus, this bombing could have been avoided.

The squadrons of RAF bombers would be led by a group of so-called Pathfinders. This group consisted of 25 Wellington, Lancaster, and Halifax aircraft. It would mark the target area by dropping flares and incendiary bombs. Next, bombers would bomb the target. This Pathfinder group had to deal with bad weather soon after the start and observed thunderstorms, lightning, electrical discharges in the atmosphere, ice build-up on the wings, and frozen bomb loads. Already at take-off, one Wellington bomber was struck by lightning, causing one of its engines to fail. The pilot returned and made a safe emergency landing after the crew had left the plane by parachute. Another Wellington Pathfinder caught fire over England, and the crew was able to leave the plane on time. The burning plane crashed into the small town of Somersham, where thirteen British citizens perished from the event.

Determining the target area of Aachen proved difficult. The planes dropped their bomb loads rather than randomly throughout the region. That included places that were often more than thirty kilometers from Aachen. Due to a change of course and bad weather, the target had become a different area than the original target of Aachen. Only 184 aircraft later reported that they had attacked Aachen. Places such as Heerlen, Brunssum, and Kerkrade were also affected. In the Geleen area, the bombs fell on all adjacent locations.

In the late evening of 5 October 1942, Geleen mistakenly been bombed. The result was a great number of people lost their lives. Due to the bad weather, the planes deviated significantly from their planned course. However, in Geleen, the approaching group of RAF bombers were spotted in time. The German Air Protection Center, located in the basement of the Geleen Town Hall, had already reported an air alarm earlier, at 9:42 p.m. After numerous flares illuminated Geleen and the surrounding area, a “major alarm” was sounded at 9:55 p.m. Immediately afterward, the bombs fell on Geleen. The town had to withstand two waves of attacks and lasted until approximately 11:10 p.m. About thirty planes carried out this inferno for about an hour. The high alarm did not get lifted until 11:55 p.m.

There were 83 deaths, 22 persons seriously injured, and 59 homes destroyed. Of the 227 severely damaged homes, 103 were ready for demolition. Furthermore, 528 houses were more or less damaged, and 1,728 houses had roof and glass damage. It caused three thousand people to become homeless.

The RAF pilots targeted mission that night was the city of Aachen, in Germany, including an area with a circumference of thirty kilometers. Flying in the direction of Geleen, the pilots imagined themselves on course to Aachen. In doing so, they almost certainly confused the States mine Maurits and its associated coking factory with the equally sized Mine Anna and the coking factory in Alsdorf. The Maurits complex is as far from the River Maas as mine Anna is, from the River Worm.

Thirteen coal miners lost their lives and the Maurits was heavily damaged in the raid. It took fire crews from several cities to help extinguish the fires caused by the bombing. Fire crews even came from Rotterdam, which is about 200 KM away from the mine, to help with the fires.

Three thousand residents were homeless, approximately twenty percent of the population. Only one plane dropped its bombs over Aachen, the actual target of the attack. A Wellington bomber crashed near Maastricht, killing five crew members. A bomber exploded during a firefight over Brunssum. Wreckage and body parts of the crew fell scattered across the municipality.

Sources

https://www.demijnen.nl/actueel/artikel/het-bombardement-op-geleen-5-oktober-1942

https://www.liberationroute.com/pois/902/lancaster-monument

https://historiesittardgeleenborn.nl/verhaal/19/het-bombardement-van-geleen

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

The Rosenboom Family

I came across this death notification of Jacob Rosenboom. The reason why it drew my attention was the date. Jacob died on 10 April 1968, the very day I was born. Then when I did more research, I discovered that Jacon had lived in my hometown of Geleen in the Netherlands.

The Rosenboom-Wolf family lived in Sittard from 1933 and in Geleen from 1936 to 1938. An Abraham Rosenbaum/Rosenboom had come to the Netherlands from Germany in the early nineteenth century and had settled in Zevenaar as a merchant. His grandson, (also named) Abraham, married Josina Wolf from Lith (near Oss) in 1895. From this son, Jacob Rosenboom was born in 1896 in Zevenaar. Jacob married his cousin Vrouwtje (which means little woman in Dutch) Wolf from Lith in 1918, also born in 1896. In Zevenaar, daughter Saartje was born in 1919, son Herman Abraham in 1920, then in Didam in 1922, daughter Josina Rebekka followed by son Levie Rosenboom in 1923. Jacob’s mother died in 1922, after which his father remarried.

The Rosenbooms were traditionally merchants by trade, but Jacob, like his uncle Nathan Rosenboom, started working in the mines in the south of the province of Limburg at a certain point.

Jacob and Vrouwtje and their four children lived in Hoensbroek in 1929, then in Brunssum and from May 1933 in Sittard. Jacob was then a carpenter by trade. In October 1936, they moved to Geleen Jacob worked in Geleen at the state mine Maurits.

The family moved back to Sittard in November 1938 at 5 Vouerweg. (The company Philips had a factory at Vouerweg, where I worked for ten years) Daughter Saartje worked as domestic help and lived (most of the time) in Amsterdam from November 1938 to July 1940 and in Arnhem from 1941-1942. During of the German invasion, Vrouwtje Rosenboom-Wolf and his daughter Josina stayed in Amsterdam for a few months. Saartje returned to Sittard in March 1942.

The family probably went into hiding in the spring of 1943 when something went wrong with daughter Saartje: she died in Heerlen on 28 October 1943, aged 24. I am a father of 3 children, and I would not know how I would feel if one of my children died. The only thing I can be sure of is that I’d be devastated.

The rest of the family survived the war. Apart from the loss of Saartje, there were more victims in the family. In 1942, Vrouwtjes’s brother Herman Wolf was deported from Sittard with his wife and two sons and gassed in Auschwitz. Jacob’s sister Regina Koppel-Rosenboom, a young widow, had been murdered in Sobibor, together with her daughter. Jacob’s father, age 74, died in Zevenaar in January 1943; Jacob’s stepmother survived the war.

After the liberation in 1945, the five surviving family members returned to the Vouerweg in Sittard. Not much later, they lived at 45 Resedastraat. After the war, Jacob worked for some time at the Julia mine in Eygelshoven. They moved to Eindhoven soon afterwards.

The sons left home and married within a few years. Herman Abraham became a draftsman at the SBB, a nitrogen fixation company. It also has significance to me. Some employees died during the war, either because they had been in resistance or due to a bombing by the RAF in 1943, where the RAF had mistaken Geleen for Aachen in Germany. A monument was erected, for these men, in the street where I grew up. I passed it by many times without giving it a second glance.

Herman Abraham married Lena Offenbach in 1952 and moved to Amsterdam with her in 1959. He passed away in 2015.

Josina Rebekka was a shop assistant until her marriage in 1953 to the divorced Amsterdam tailor Tobias Lavino. She then left for Amsterdam. They had two children. Josina passed away in 2009. Levie Rosenboom became a miner and married Neeltje Groot in 1950. They had two children in Sittard and moved to Boxtel in 1957. Levie died in 2003 in Boxtel.

After Jacob and Vrouwtje celebrated their 40th wedding anniversary in Sittard in 1958, they followed their daughter and eldest son to Amsterdam in November 1959, where Jacob died on April 101968 and Vrouwtje in 1980.

Amazingly, all of this originated and in my hometown in an area I am very familiar with, and I never knew until today.

sources

https://www.stolpersteinesittardgeleen.nl/Stichting

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/nl/page/666557/familie-rosenboom

Honoring Heroes From Geleen

It is important to tell the stories of those who collaborated with the Nazis. Regardless of what some governments want you to believe, there were collaborators in all occupied countries. Some were even more evil than the occupiers.

However, it is equally important to honour those who helped their fellow citizens, often at risk of their own lives.

Jan Michiel Peters married Maria Wilhelmina Roberts on 27 August 1937 in the town of Geleen, in the province of Limburg in the Netherlands. Little did they know then how life would change for them within a few years.

When Gienga Keizer’s father was arrested and deported in 1942, she was forced to move from Utrecht to Amsterdam with her mother, sister, and brother. There, the family made contact with the Amsterdam Student Group* (ASG), which arranged hiding places for the Keizers in Limburg. After moving between various locations, Gienga Keizer (later Shimonowicz) was sheltered by the Peters family in Geleen. Jan Michiel Peters, who lived with his wife, Maria, and two daughters, made a modest living as a miner. The family also sheltered several other Jewish refugees for short periods. Whenever a raid was imminent, Gienga was brought to stay with relatives of the Peters family in other villages. aria Peters also helped Gienga stay in touch with her family, who were hiding in the same area. The Peters family acted out of purely humanitarian principles and always treated Gienga as another daughter. After the liberation of Limburg, the family immediately tried to reunite Gienga Keizer with her surviving family. Gienga maintained a close relationship with her rescuers, and their daughters and grandchildren. After she immigrated to Israel, she returned to the Netherlands to visit the Peters family and their daughters came to see her in Israel.

On 15 July 1981, Yad Vashem recognized Jan Michiel Peters and his wife, Maria Wilhelmina Peters-Roberts, as Righteous Among the Nations.

I was 13 when the Peters were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations, and I was oblivious to that fact.

Hendrik and Hiltje Douwes lived in the town of Geleen, Limburg. Hiltje’s brother and his wife, the Hofstedes, also lived there and both couples were active in the hiding of Jewish children throughout the area. The Hofstedes hid Henny Kalkstein, a six-year-old Jewish girl whose parents had fled from Poland. She was brought to them from Amsterdam by the NV group in 1943 with her brother Ronnie, who was hidden in another village. It sometimes became dangerous for the Hofstedes to hide Henny when there were searches in the area, so they moved her for shorter and longer periods to other families, but mainly to the Douwes. The child liked being with her “cousins,” who had a baby. They treated her like part of the family. In her testimony to Yad Vashem, Henny recalled that they did this without any compensation and out of purely humanitarian motives. At the end of the war, Henny returned to her parents after they had gotten back on their feet financially. She kept in close contact with the Douweses and the Hofstedes even after she moved to Israel.

On 16 February 1984, Yad Vashem recognized Hendrik Douwes and his wife, Hiltje Douwes-Hofstede, as Righteous Among the Nations.

Hendrik and Hiltje lived long lives and were buried in the Lutterade cemetery in Geleen.

I was born in Geleen and had not heard of these brave souls.

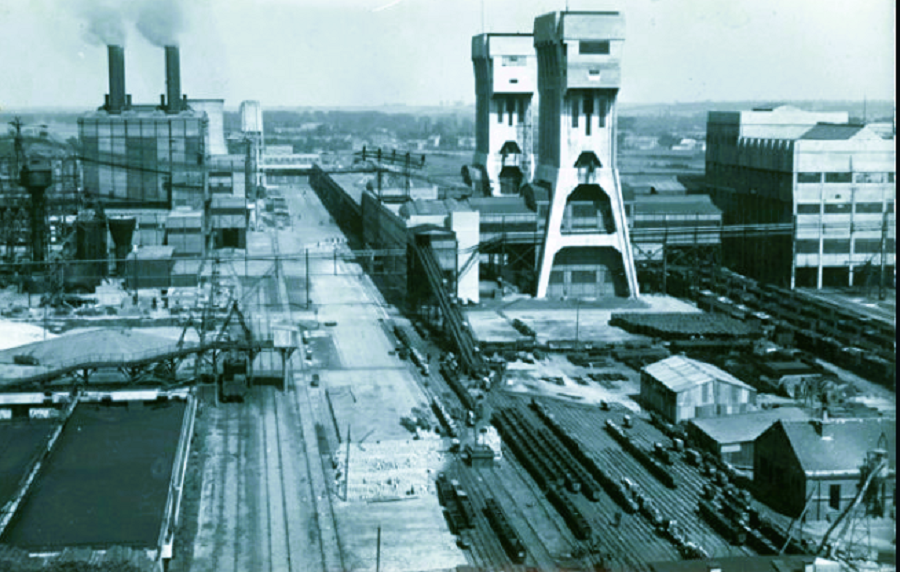

Remembering the Jews of Geleen

The photograph above might appear strange for a Holocaust story, but I posted it for a good reason. It is a chemical plant called DSM. At the edge on the top of the photo, you can see a few apartment blocks where I grew up, in the town of Geleen in the Netherlands.

The DSM was a daily reality for me. When I looked at it again today, I realized that there were several fellow-Geleen citizens that would have loved it if that chemical plant, ugly as it was, had been their daily reality. They never saw it because they were murdered. Below is a small poem I wrote for them a few years ago and the names of those murdered.

You are not different from me.

You eat the same food.

You read the same books.

But yet you are not free.

You are not free because of someone’s idea of you.

You are given a yellow star.

You are catalogued and numbered like cattle.

But yet you’re not an animal but a human too.

You are being killed in the vilest of ways.

You are a man, a woman, a child, a parent.

You are erased as if you were never here.

But yet you are remembered on many days.

You are not different to me but you are also not the same.

You are merely a number and a name on a list.

You are not listened to for you have no voice

But I pledge I will shout for you in loud acclaim.

| Last name | First name | Born | Died* | |

| 1 | Freimark-Adler | Hermine | 12-12-1876 Urspringen (D) | 14-05-1943 Sobibor |

| 2 | Baum | Max | 04-01-1907 Bauchem (D) | 31-03-1944 Auschwitz |

| 3 | Cohen-Ten Brink | Esthella Carolina | 05-06-1904 Ootmarsum | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 4 | Meyer-Cahn | Jeanette (Jetta) | 18-12-1859 Leutesdorf (D) | 10-05-1943 Westerbork |

| 5 | Claessens | Albert | 19-04-1905 Obbicht | 30-04-1943 Midden-Europa |

| 6 | Cohen | Frieda | 11-07-1924 Vaals | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 7 | Cohen | Henny | 30-10-1925 Vaals | 26-09-1942 Auschwitz |

| 8 | Cohen | Josephine | 09-07-1930 Geleen | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 9 | Cohen | Simon | 01-05-1889 Midwolda | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 10 | Freimark | Ernst | 12-08-1936 Frankfurt (D) | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 11 | Freimark | Friedrich | 27-10-1902 Marktheidenfeld (D) | 30-04-1943 Midden-Europa |

| 12 | Freimark | Kurt | 21-12-1939 Heerlen | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 13 | Levy-Goldschmidt | Irene | 15-02-1907 Rheda (D) | 30-11-1943 Auschwitz |

| 14 | Goldschmidt | Josef | 24-10-1867 Rheda (D) | 28-05-1943 Sobibor |

| 15 | Goldsteen | Frederik | 09-07-1918 Rheydt (D) | 15-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 16 | Levi-Harf | Rosalie | 27-10-1880 Mönchengladbach (D) | 28-05-1943 Sobibor |

| 17 | Goldschmidt-Jacob | Frieda | 19-02-1869 Rheda-Wiedenbrück (D) | 07-10-1943 Maastricht** |

| 18 | May-Jacobsohn | Klara | 14-05-1871 Neckarbischofsheim (D) | 14-05-1943 Sobibor |

| 19 | Meyer-Kaufmann | Berta | 03-01-1912 Köln (D) | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 20 | Kaufmann | Margard | 10-11-1928 Gronau (D) | 03-09-1943 Auschwitz |

| 21 | Kaufmann | Richard | 30-06-1886 Moers (D) | 03-09-1943 Auschwitz |

| 22 | Heimberg-Klestadt | Bertha | 28-12-1891 Büren (D) | 25-01-1943 Auschwitz*** |

| 23 | Claessens-Krzanowska | Ajga | 17-03-1909 Zawiercie (Polen) | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 24 | Lebenstein | Ida | 16-05-1888 Ochtrup (D) | 28-05-1943 Sobibor |

| 25 | Levy | Arnold | 27-05-1880 Wuppertal-Elberfeld (D) | 28-05-1943 Sobibor |

| 26 | Levy | Hans Erich | 22-03-1911 Düsseldorf (D) | 31-03-1944 Polen |

| 27 | Löwenfels | Luise | 05-07-1915 Trabelsdorf (D) | 30-09-1942 Auschwitz |

| 28 | Freimark-May | Gertruda | 16-02-1902 Niedermendig (D) | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 29 | Winter-May | Irma Johanna | 30-08-1908 Niedermendig (D) | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 30 | Goldsteen-Mendel | Carolina | 06-07-1880 Tetz (D) | 22-10-1943 Auschwitz**** |

| 31 | Meyer | Max | 23-01-1900 Remagen-Oberwinter (D) | 30-04-1943 Midden-Europa |

| 32 | Roer | Helene | 14-09-1921 Zülpich (D) | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 33 | Roer | Ilse | 20-02-1925 Zülpich (D) | 31-08-1942 Auschwitz |

| 34 | Baum-Salmagne | Sophia | 12-06-1867 Eilendorf (D) | 16-11-1943 Bergen-Belzen |

| 35 | Willner | Paul Siegfried | 05-06-1902 Aachen (D) | 30-04-1943 Midden-Europa |

| 36 | Winter | Gustav | 01-11-1897 Korschenbroich (D) | 30-04-1943 Midden-Europa |

| 37 | Kaufmann-Zilversmit | Adele | 07-12-1890 Gronau (D) | 03-09-1943 Auschwitz |

The Residents of Peschstraat 28, Geleen—All Murdered

I could call this history on my doorstep. The Peschstraat in Geleen is a street that is well known to me. Although on the other side of town, I did go there often to visit friends living on that street or nearby. Though, I knew little about one family who lived on that street. The family was murdered during the Holocaust. Via The Simon Wiesenthal Genealogy Geolocation Initiative, I came across the story of the Freimark family.

https://simonwiesenthal-galicia-ai.com/swiggi/?z=20230228043842

In 1817, three Freymark families lived in Homburg am Main (located between Frankfurt and Würzburg). Salomon Freimark, 14, moved with his parents from Homburg to Marktheidenfeld in 1887 and started a blacksmith shop there in 1901. He married the tailor Hermine Adler from nearby Urspringen around 1898. They had four sons, the third of which was Friedrich, born in 1902. Salomon died in 1911, after which Hermine earned a living with a “Kurz-, Weiss- und Wollwaren-Geschäft.”

Friedrich married Gertruda May from Niedermendig (near Koblenz) in Frankfurt in August 1935. Gertruda had another sister and brother; her father had died in 1933, and her mother was still alive.

One year later, their son Ernst Freimark was born in Frankfurt. His parents decided not much later to leave Germany. In May 1936, Aunt Irma and Uncle Gustav Winter-May had moved to Geleen, where Gustav had a launderette and hot iron company. The childless couple took Grandma May in November 1936, and in the spring of 1937, Ernst and his parents also came to Geleen. Father Friedrich became uncle Gustav’s partner in the clothes laundry. In April 1938, Grandma Freimark also came to live with the family in Geleen. Kurt Freimark was born in Heerlen in December 1939 and became the eighth family member at Peschstraat 28.

Six months later, the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands happened. The family underwent gradual introduction measures to isolate and exclude Jews. In February 1941, they had to register and then by June 1941, they were no longer allowed to enter public places. Ernst was not allowed to go into public places in September, not even school. All eight lost their German nationality in November 1941.

For Employment in Germany program, six of the eight residents of Peschstraat 28 were ordered to report on 25 August 1942. The two grandmothers (ages 65 and 71) were left behind at the residence. Uncle Gustav and his father tried to get an extension using an argument about having 300 kg of laundry that needed to be taken care of but to no avail. The two couples and their two children, along with many others, were transferred via Maastricht to Westerbork and then deported to Auschwitz on 28 August.

An hour before they were due to arrive, the 18-55-year-old men, were separated from their wives and children at the Kosel Labour Camp. Friedrich Freimark and Gustav Winter were placed in labour camps with their fellow sufferers from Kosel. The women and children were gassed immediately upon arriving in Auschwitz on 30 or 31 August—Gertrude with her sons, six-year-old Ernst, two-year-old Kurt, and sister Irma.

The death dates of Friedrich Freimark and Gustav Winter were later formally set by the Red Cross as 30 April 1943, somewhere in Central Europe. The exact day, place and circumstances have never been clarified.

The two grandmothers who had remained behind were arrested in early April 1943 and taken to the Vught Camp with the last Jews remaining in Limburg. After, they were deported via Westerbork to Sobibor Extermination Camp, where they were gassed to death on 14 May 1943.

In June 1943, “De Limburgsche” Stoomwasscherij was located at Peschstraat 28, which was still there after the war. The Maurits Clothing Laundry of Gustav Winter and Friedrich Freimark was officially closed on 27 October 1947. None of the family had returned.

https://www.stolpersteinesittardgeleen.nl/Slachtoffers/Kurt-Freimark

https://www.joodsmonument.nl/en/page/137516/kurt-freimark

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.