On April 15, 1945, British forces, including units of the British Second Army and the 11th Armoured Division, entered Bergen-Belsen and liberated the remaining prisoners. The sight that greeted the liberators was horrifying. They found tens of thousands of emaciated and diseased prisoners, along with thousands of unburied corpses strewn throughout the camp.

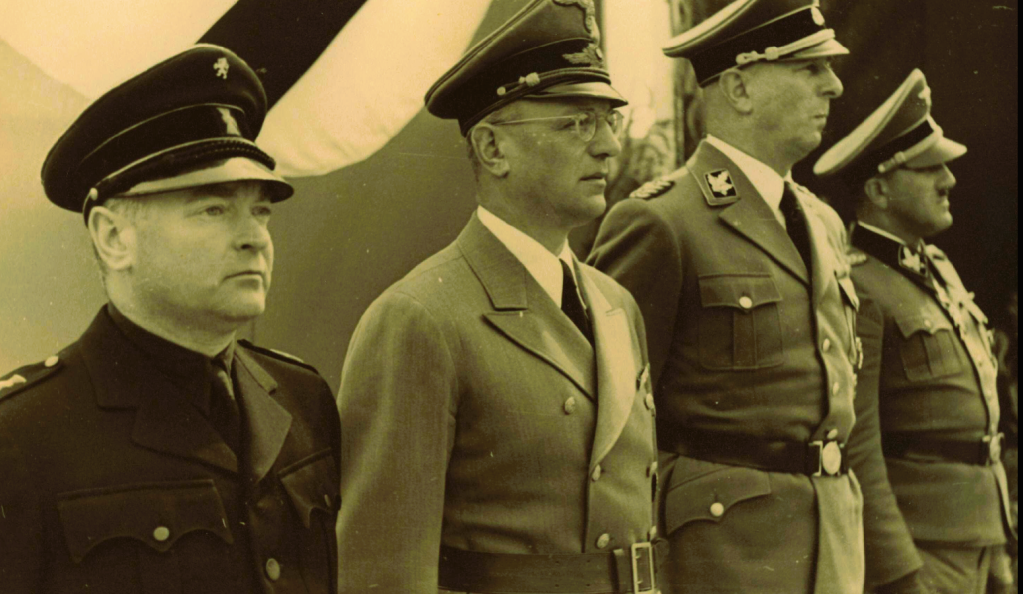

The liberation of Bergen-Belsen brought the horrors of the Holocaust to the attention of the world in a particularly stark and poignant manner. Images and reports from the camp shocked the world, revealing the true extent of Nazi atrocities and the human suffering inflicted upon millions of innocent people.

Following the liberation, efforts were made to provide medical care, food, and sanitation to the survivors. However, despite these efforts, many prisoners succumbed to disease and malnutrition even after their liberation.

I was going to include photos of what the liberators found that day, but although a picture tells a thousand words—it never tells the full story, Therefore following are testimonies of some of the liberators.

Dick Williams: “But we went further on into the camp, and seen these corpses lying everywhere. You didn’t know whether they were living or dead. Most of them were dead. Some were trying to walk, some were stumbling, some on hands and knees, but in the lagers, the barbed wire around the huts, you could see that the doors were open. The stench coming out of them was fearsome. They were lying in the doorways – tried to get down the stairs and fallen and just died on the spot. And it was just everywhere.

Going into, more deeper, into the camp the stench got worse and the numbers of dead – they were just impossible to know how many there were…Inside the camp itself, it was just unbelievable. You just couldn’t believe the numbers involved… This was one of the things which struck me when I first went in, that the whole camp was so quiet and yet there were so many people there. You couldn’t hear anything, there was just no sound at all and yet there was some movement – those people who could walk or move – but just so quiet.

You just couldn’t understand that all those people could be there and yet everything was so quiet…It was just this oppressive haze over the camp, the smell, the starkness of the barbed wire fences, the dullness of the bare earth, the scattered bodies and these very dull, too, striped grey uniforms – those who had it – it was just so dull. The sun, yes the sun was shining, but they were just didn’t seem to make any life at all in that camp. Everything seemed to be dead. The slowness of the movement of the people who could walk. Everything was just ghost-like and it was just unbelievable that there were literally people living still there. There’s so much death apparent that the living, certainly, were in the minority.”

Harry Oakes: “About that time the chaps attached to 11th Armoured Division had seen a staff car come up to headquarters one day with a German officer, or two German officers I believe, blindfolded. And when they made enquiries they were told that they were from a Political Prison Camp at Belsen.

The Germans, anticipating us capturing the camp or over-running it, wanted the British to send in an advanced party to prevent these prisoners who were supposed to be infected with typhus from escaping. But the force we wanted to send in was too much. The Germans felt it wouldn’t have been fair so they agreed on a compromise that they would leave 1,000 Wehrmacht behind if we returned them within ten days. So we were standing by at Lüneburg, Lawrie and myself, to go into Belsen.”

Bill Lawrie: “We had this business of the staff car with the white flags telling us that there was a typhus hospital on the way ahead of us, and would we be willing to call a halt to any actual battle until this area was taken over in case of escapees into Europe and the ravage that would take place.

And as far as I know, the Brigadier believed this story, and we set sail that evening to have a look at this typhus hospital under a white flag. And there was no typhus hospital. There was barbed wire, sentry boxes, a huge garrison building for SS troopers, and Belsen concentration camp. And, as I say, we drove up in two, three jeeps, four jeeps maybe, in the evening, and we saw this concentration camp that we believed was a

typhus hospital. But we knew immediately that it wasn’t a typhus hospital.”

Gilbert King: “I can remember going down this road with these Hungarian guards, soldiers, all got their bullets and grenades on their chest. We went in then to a very large military hospital and parked our vehicles for the time being and we was told that we would be going up to relieve the camp in the morning. And our Troop, which was C Troop, were the first up there to enter the gates. A medical team had gone through the gates, but we were the first military, and we had to round up the German military. One thing that I remember vividly was after entering the camp, you’d see the inmates which weren’t too bad – they got worse as they went down the camp – and as I stood there this, I don’t know if it was a man or a woman you couldn’t tell really, came up to me and kissed my boots. And it nearly brought tears to me eyes. It was very emotional.”

William Arthur Wood: “And then on the left hand side there were the huts and of course outside the huts were piles and piles of dead bodies, and living ones, we didn’t know which were which. In the huts themselves, equally, you didn’t know who was dead and who was alive unless they made, there was some movement you could see, because the dead and the living were all together – they hadn’t the energy to take the dead out and there were so many piled outside as I say that it was hard to see, to pick out the dead from the living…”

BBC recording from April 20, 1945 of Jewish survivors of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp singing Hatikvah, today the national anthem of Israel, only five days after their liberation by Allied forces. (The words sung are from the original poem by Naftali Herz Imber.)

Ending with a quote from Margot Frank, one of the victims who was not liberated, but perished a few weeks earlier together with her younger sister, Anne Frank. I used this quote a few years ago in a speech for my eldest son‘s high school graduation, as a representative as the parents council.

“Times change, people change, thoughts about good and evil change, about true and false. But what always remains fast and steady is the affection that your friends feel for you, those who always have your best interest at heart.”

Sources

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-liberation-of-bergen-belsen

https://www.azquotes.com/quote/733167

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bergen-Belsen_concentration_camp

Donation

I am passionate about my site and I know you all like reading my blogs. I have been doing this at no cost and will continue to do so. All I ask is for a voluntary donation of $2, however if you are not in a position to do so I can fully understand, maybe next time then. Thank you. To donate click on the credit/debit card icon of the card you will use. If you want to donate more then $2 just add a higher number in the box left from the PayPal link. Many thanks.

$2.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.